Director Ralph Richardson’s Work-In-Progress Explores Race, Class And Romance – Taking Audiences Deep Into The Heart Of America.

By Eisa Nefertari Ulen, published in Horizon Magazine, May 2000

When I met Ralph Richardson, he told me he was working on a film – not the biggest deal in the world to a woman living in Fort Greene, Brooklyn. Here, every other resident is working on a screenplay, or a collection of poetry, or a feature magazine article, or something or other. This is the home of the New Black Renaissance – what Harlem was to the 1920s and 1930s. Richardson (no connection to the legendary British film star of the same name) moved to New York from Philadelphia for the same reasons every other immigrant moves here: to make it.

He found an apartment in Fort Greene and dove right into the pools of creative talent that make this community happen. I thought I’d simply take a look at his script and offer feedback, maybe write a piece on making movies for horizon. Well, I am pleased to report both the script and the promotional trailer he shot captivated me – much like Richardson himself. He is, now, my very significant other – something you need to know, dear reader, for the love of journalistic integrity as well as the love of love.

Richardson remains hard at work on his first feature film, When Tyson Met Tyra. Wu Tang Clan’s RZA is producing this romantic action-adventure flick, which stars Shao-Lin’s Ghostface. Writer/producer/director Richardson says, “I make films for me, and I’m critical as hell. I also ask myself, ‘Would I wanna pay $10 for this?’ That makes me raise the bar.” This movie also raises issues about race, generation, home – issues about America. But, Richardson claims, these subjects sprang organically from the scriptwriting process. “I do what I like. As an artist, you have to do what you love. Then you put it out for people to consume. If they don’t like it, they’ll spit it back in your face. If they like it, then they’ll eat more.”

A graduate of Widener University in Chester, Penn., Richardson was accepted by Georgetown Law, but never attended, opting instead to act in a “funny propaganda movie” set in WW II China, called Narrow Escape. After that three-month gig, Richardson moved to Brooklyn, where he wrote, produced, directed, and edited Kharja, winner of a 1997 New York Independent Film Monitor Award. Then Richardson wrote, produced and directed Chocolate, another short. Not only will When Tyson Met Tyra be the first film he hasn’t shot right outside his apartment building on Fort Greene Place, this feature positions Richardson to play the reel-deal Hollywood game.

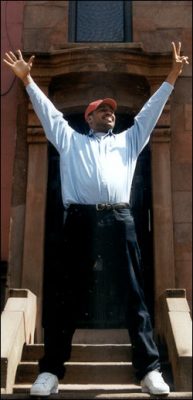

BET’s Starz!3 will feature Richardson and Kharja later this spring. Viewers will glimpse 6 feet and 4 inches’ worth of the affable charm and winning smile for which I praise the Lord each and every day, and they’ll peep clips from his winning short. Everyone seems to be tapping into the power of the motion picture industry – and the young talent driving celluloid into the next century. Thirty-one-year-old Richardson urges any new creative energy out there to help transgress the old Hollywood boundaries that have historically limited big-screen American images.

w h a t s p i k e l e e d i d

Black filmmakers have captivated audiences around the world since Spike Lee had to have it. Despite Blaxploitation films of the 1970s and groundbreaking cinema like the work of Oscar Micheaux, before Lee’s cutting-edge indie, most movie-going audiences in this country were as segregated as a 1950s Birmingham bus. The themes Richardson explores in his script should take filmmaking – and film audiences – to a new level.

Richardson says he “just wanted to do a film about love, deep love, which is going through those fires, to know you love each other.” But the film also “resonates on a lot of themes.” Ghostface’s character, Tyson, tries to save his mother’s house, which has been in the family for 100 years. For Richardson, this home represents that 40 acres and a mule promised to former slaves during the Reconstruction Era following the Civil War. While that was one of many broken promises this country made to former slaves, Tyson’s family took it for themselves – the fattest slice of the American dream pie.

“Tyra’s father is White,” Richardson continues. “He symbolizes the institution of America, and he has a mulatto daughter, like maybe a slave owner would. But this is 1999, so he’s with her, but at the same time he’s corrupt.” Judge Halt loves his daughter, but his divorce from Tyra’s Black mother and the death of Tyra’s brother all work against family cohesion. An A-student who’s skipping school just before she’s set to graduate, “Tyra’s breaking away from Daddy, but he’s not really listening, ’cause,” rather than serving justice, “he’s on the phone making deals.” Richardson explains, “Tyra is a rich girl who’s never dated a Black guy, ’cause her father won’t let her. But he only dates Black women.”

She runs into the arms of Tyson – away from the deep complexities of her home life, and the patriarchal judge sends a White private detective after the only child he has left. This sets what might have been an urban movie on the road, into the heart of America.

“If I was a filmmaker 20 years ago, I still would have done it this way,” Richardson claims. He doesn’t think his work is controversial, just that these are themes that haven’t been explored for today’s audiences. The dichotomies in his plot drive the movie forward. “I like things with an edge, raw. The polarities will set off a charge.” Certainly the image of a Black woman calling a White man Daddy will set something off in theaters once When Tyson Met Tyra is in the can.

‘ j u s t k e e p s h o o t i n g ‘

Richardson advises aspiring filmmakers to set off their own celluloid dreams. “Grab a camera and go do it. Just keep shooting and get better. You’ll learn more by doing your own films than anything else.” He also cautions young artists to remember the economy of the industry. A filmmaker should want all partners to make a profit, to feel good about the work. Take the time to think about your budget, about how much your investors are going to get out, against what they put in to a project. Richardson wrote When Tyson Met Tyra with a low budget in mind and adjusted as more money poured in to fuel the work.

“We have resources, and you can get great actors if you have a great script,” he insists. “The first thing is you’ve got to know how to write a story. That’s the blueprint, the architectural design. You have to be able to transfer feeling. People feel the truth. That’s the intangible aspect of films: Do people feel it?” Once any artist perfects the craft of story, everything he or she needs will be drawn to the talent, to the aesthetic product. Be conscious of that power. “Entertainment is where people want to put their money to make money.”

Inspired by screenwriter/directors Robert Rodriguez (El Mariachi) and Quentin Tarantino, Richardson also knows “Spike paved the way” for new African-American filmmakers like himself, “because he was independent.” Black directors of the ’80s and ’90s like John Singleton “showed that we can do it.”

Despite the perils of any big-money industry, the rim of opportunity is wider than ever in Hollywood. But Hollywood is also notorious for flashing lights and movable sets, for making fantasy real, for crafty manipulation. “There’s no magic,” Richardson intones. If you want to make movies, “just start from wherever you are and move.”