Originally appeared on Truthout.org –

Originally appeared on Truthout.org –

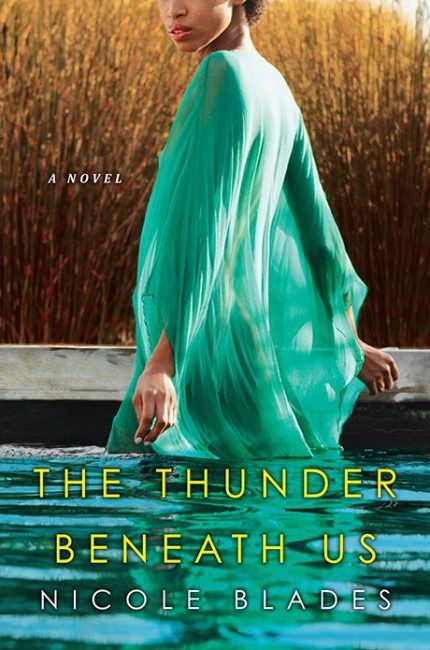

Breaking the Binaries: “The Thunder Beneath Us”

By Eisa Nefertari Ulen | Interview | January 2, 2017

Nicole Blades’ second novel, The Thunder Beneath Us, centers and elevates Black female life while remaining authentic to the experiences of ordinary Black girls. That is a tricky path, and Blades, a novelist and freelance journalist, walks it well. Her female protagonist, Best Lightburn, is a witty gem of a character who can cuss Sam Jackson under the table, then gracefully select the right fork to use. Black female life hovers between binaries like these: We are either bourgie or ratchet, educated or street, virgins or whores. Of course, this is ridiculous. This twoness has dangerous ramifications in its reinforcement of marginalization and division. Yes, we are #BlackGirlMagic, but we are also #SayHerName. Where do the binaries leave Black girls in the middle?

For most of us, like humans everywhere, we are each binary simultaneously. Or neither. Like Best, we know which fork to use and also which well-placed curse to use. We can also decide the table itself is no longer a place where we wish to sit. But choices like these are hard to make. Blades is unapologetic as she develops a full, rich, round character with flaws and sudden attitude who is sometimes not so nice. Best is also a character who is loving and caring and vulnerable and always captivating. And there is a reason she is sometimes not so nice.

In the perfectly crafted prologue, a frozen lake that Best and her two brothers attempt to cross while walking home on Christmas Eve cracks, opens, pulls all three under. The siblings plunge into the waters, but only Best claws her way out. She is the only one to survive. No wonder Best sometimes makes poor choices. She has felt the icy claws of death roll and roil under her thrashing body, but escapes death to roar her anguish into the night air above. Survivor’s guilt haunts her like an actual ghost. In the aftermath of her survival, Best begins to believe that she’s the worst. She is not alone in her anguish. Her parents are also suffering with varying iterations of mental decline because of the emotional toll of their suffering. Best’s friends, all New York shine and sophistication, have no idea that their queen bee bestie has such a tragic secret buried in her unconscious mind. Her sometimes erratic behavior, compelled by a series of events that act as triggers to the frozen lake tragedy, confuses and alienates them.

This novel is so cinematic, I couldn’t help but think of a small-screen phenomenon as I read it. “Empire,” the hit Fox television show, is populated by characters who spin through various cycles of deviance as they claw the world, and sometimes each other, to stay on top of a family business that feels as delicate as the thin ice Blades’ characters walk in her novel. Yet, “Empire” also examines themes provocative and meaningful and too often silenced in the Black community, including mental health.

Blades’ novel is like the Kehinde Wiley art that decorates the first season of Empire. She takes the street culture of Black people and elevates it with her lyrical prose. But this Black street culture is not monolithic. With Best’s Trinidadian background, her biracial boyfriend, a gay bestie who introduced them, and twin South Asian sister friends, Blades has populated her novel with characters that look like the real New York — indeed, the real world all around. If this diversity in what were formerly majority-white continents has fueled the rise of fascism in Europe and the United States, then more white people need to read books with Brown characters like Blades’s.

As Best side-eyes her overwhelmingly white coworkers at the magazine where she works as a columnist, she interrogates the segregation in media and publishing that is so problematic in the real world. Movements to liberate media and publishing from this overwhelming whiteness have gained some traction; most successful among them, perhaps, has been #OscarsSoWhite. But there are others, including a strong movement for more diversity in children’s books called #WeNeedDiverseBooks.

Blades and I discussed this effort and her personal experience as a writer, as well as the book itself, The Thunder Beneath Us, which I urge you to read. Blades examines mental health, Black families, religion, rage and race in this novel which is as page-turningly engaging as it is ambitious and substantive. The Thunder Beneath Us is accessible and often fun, yet meaningful and reliably substantive, breaking the binaries, the twoness that can only reinforce division, and offers a kind of bridge to become whole.

Truthout: The Thunder Beneath Us is a terrific novel. Where did the idea for the story come from?

Nicole Blades: Glad you enjoyed the read. Some years ago, I read a magazine story about these three brothers who went duck-hunting as part of their Christmas tradition. But it all turned tragic when the family dog accidentally punched a whole in the lightly frozen lake. And while trying to save the dog, all three brothers were sucked down into freezing water. Two of the brothers drowned and one survived. The story really stayed with me. I kept thinking about the level of guilt the one surviving brother probably carried, and how that kind of torment could really alter how he sees himself moving forward. Although the brothers were grown men when the accident happened, I started wondering how that heaviness and guilt would translate to someone who was just a teenager when their life fractured apart.

Your prologue is a lovely feat of literary power. I imagine you writing it much like Best, your female protagonist, writes her big article while in Canada. Did it pour out of you in one of those wonderful moments of inspiration all writers covet?

Wow. Thank you! It actually did. Once I got the mood of it set, I was able to just write it straight through.

How much of Best’s story is your story? You are both Canadian-born writers living in the United States. Best works at a major magazine and you’ve worked at Essence, Women’s Health and ESPN magazines. Are there any other significant autobiographical aspects to your novel?

As the Nora Ephron saying goes, “everything is copy!” With this story, there are many aspects drawn from real people and real issues that I’ve pulled apart, reconfigured and Frankensteind into other intriguing storylines, other characters and other quirks. Part of the fun for former colleagues is trying to guess from whom some of the “source material” comes. Ha. As for Best and me, there are definitely similarities: we’re both Montrealers living in Brooklyn, both work at magazines, but this is not a veiled memoir. She is not me — thankfully!

There are many important themes in Thunder, but mental health figures most prominently. What compelled you to examine the various iterations of mental health challenges in your characters?

What compelled me was real life. I know so many people near and dear who are dealing with various mental health challenges. It all needs to be normalized, because it is very much that. Mental health issues and illness in our communities are normal and common and real, and need to be considered. Drop the shame and secrets around all of it; that kind of weight helps no one.

Did you wear your journalist’s cap and conduct a bit of research about mental health in the Black community at any stage in the writing process?

I did a lot research on various things in writing this novel, and mental health in the Black community was definitely one of them. I wanted to get it as right as possible. Authenticity, verisimilitude, are important to me.

There is a brief reference to “Sex and the City” in your novel, but Thunder does such a better job of capturing the real New York — with characters of many colors living and working and riding the subway together. Best’s fabulous New York life is multihued. Was layering the story with characters of diverse ethnicities and religions important to you?

Absolutely. I want to tell stories that are reflective of real life. The New York I lived in has people of different hues and cultures riding the subway together. When I think about the writers who have most impacted my writing — Toni Morrison, Alice Munro, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Jhumpa Lahiri, Junot Díaz, Edwidge Danticat and [others] — they’ve done so by being focused on telling rich, real stories that aren’t coming from some “default” position of all white, all well-to-do, all American. It’s not that single, same story.

These writers create worlds lived in by 3D characters who oftentimes move and feel and look like me or my friends or family. They bring these self-actualized people to life right there in the center of the page instead of maybe — maybe — squeezed up in the margins or standing around blurred out in the background. Some of these writers are also telling authentic stories starring people who look nothing like me. Characters who walk and talk with a cadence and rhythm that might be completely foreign to me, but it’s still complex and human, so real that it’s utterly captivating. They leave me eager to shape-shift and sink into some other world, time or space. They are lending us a sharp lens to look at this life from another angle. That’s impact. That’s influence. It’s meaningful.

Despite the various backgrounds of many of your characters, Best’s work life is decidedly white — and an accurate reflection of the overwhelmingly white world of New York media, including book publishing. How would you describe the real-world media and book publishing industries in terms of race?

There’s been a lot of conversation lately about the whiteness of TV writers’ rooms and #OscarsSoWhite and the overall lack of diversity in the industry. Anyone who has worked in the [New York City] media circuit knows that this has long been the case for publishing, too. The number of writers, editors, content creators of color do not match the racial and cultural make-up of those who are consuming this same media.

When it comes to magazines, maybe the “diversity” percentages aren’t as stark as they are for other industries like technology or television, but I have definitely been to my share of magazine editorial meetings where I’m The Only One or One of Few women of color seated at the table, essentially tasked with representing a whole culture and speaking up for a whole group — that is no way a monolith — ensuring that we are heard, seen and considered. It’s pressure. It creates a low-grade anxiety to be a watchdog, when that’s not what you signed up for, frankly.

How would you describe the state of Black women’s literature in particular?

This is one of those “over drinks” conversations. Ha! I’ll say this: it’s hard out here for us. We have inspired, important, meaningful, imaginative stories to tell, but some people in positions of power and influence would almost have us believe none of that is true. It’s frustrating and can hurt your feelings at times.

There have been a few campaigns to get more diverse stories out there, especially children’s books and YA [Young Adult] novels. You are a mother and have a blog dedicated to parenting called MsMaryMack.com. Do you find yourself wishing there were more books featuring Black and Brown children?

Goodness, yes! All the time. I wrote an essay for The Washington Post last year talking about the lack of diversity in everything from books to greeting cards. I said that “having brown faces in the foreground counted, seen and relevant, strikes out against the usual erasure story that has persisted for decades, the one in which black lives don’t matter, they don’t even leave a mark.” And though there has been some improvement (I just bought some children’s books starring little Black girls for my nieces for Christmas), there is still so much room for more, to do better.

How has the recent presidential election impacted the way you think about parenting and your family? Is your home country of Canada looking like the move right about now, or are you and your husband committed to life in the States regardless of the direction the country is heading?

To be honest with you, I’m still reeling from this recent election and the galling news that keeps spinning out in the aftermath. That day after the election, I had to fight back tears as I told my son who was declared the winner. That whole day-after was rough. I felt dismayed and deflated, crushed. There was a “we need to move to Canada” moment, for sure. But my husband called me back from the ledge, reminding me that now, more than ever, this country needs people like us to stay, to stand and shine that bright light on injustice, call it out and fight it with all that we have.

You are the author of another novel, your first, called Earth’s Waters. Are you at work on a third?

I just finished writing my book back at the start of September. It’s another story about secrets, family and negotiating very tangled relationships. But this has a race piece to it that is heavy and important. At its heart, this next book is about identity and the lengths we’ll go to construct and protect our ideal selves. It will be out November 2017!

Published on Truthout.org by Eisa Nefertari Ulen, January 2, 2017.