An edited version of this appeared on TheDefendersOnline.com.

An edited version of this appeared on TheDefendersOnline.com.

On December 6, 2009, the founding members of RingShout: A Place for Black Literature hosted a literary salon. The topic of our discussion: The Presentation of Black Pathology in Books and Film. The narratives: Erasure by Percival Everett and Push by Sapphire. The film: Precious. Our special guest, the woman who braved the first Brooklyn cold snap of the season to take on our heated discussion: Lisa Cortes, Executive Producer of the movie that has left some viewers in horror, others in tears, and gotten everyone talking. Or aim: To elevate the discourse around the movie, the novel, and, of course, that now infamous bucket of fried chicken.

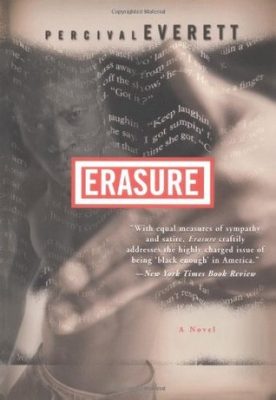

RingShout founding member Martha Southgate suggested this salon topic about two months before the November 6 release of Precious. She thinks that Everett’s Erasure is a powerful response to books like Sapphire’s, which earned the poet-turned-novelist a $500,000 advance and was excerpted in The New Yorker when it was published in 1996. Because Everett’s novel takes on the publishing industry’s response to books that explore black pathology, Southgate believes the two should be read together.

Aiming for an inter-textual reading meant the discussion would examine the conversations the novels have with each other. What does Erasure say to—and about—books such as Push?

Another question on the minds of the 30 or so artists, writers, filmmakers, and educators who attended our salon was, what does the success of Push say to—and about—African-American authors who explore other aspects of black life through their work? Some in the blogosphere have suggested that stories like Push/Precious shouldn’t be told at all. While we discussed many of the responses to Precious that had been lighting up cyberspace since the film’s November release, as culture workers we tried to focus our discussion on the ways story-tellers and image-makers bear witness to things that hurt us most.

How do we present our most painful truths?

Some in the blogosphere have suggested stories like Push shouldn’t be told at all. Most who spoke up at our RingShout salon disagreed. The issues, for us, were how these narratives are marketed and what the response of the reader / audience to this particular novel-turned-film means.

There was more general agreement that Push should not be confused with Street Lit, because, unlike the limited character development found in most Street Lit, the reader gets to know Precious, what motivates her, how she feels, her interior space. While most of us enjoyed Push, we mostly agreed that, while ambitious, Sapphire’s novel does not achieve the level of success of authors like Toni Morrison and Alice Walker, who have also explored black pathology in their fiction, and so doesn’t quite fit in the black female literary canon either, for many reasons.

One important flaw cited by Southgate, who moderated the discussion of the novel, raised the question of Sapphire’s erasure (no pun intended) of other characters’ backgrounds and motivations. What did Precious’ abusive parents experience before she was born? Were they molested or otherwise abused? Unlike Cholly in Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye and Mister in Alice Walker’s The Color Purple, Precious’ father is a flat character that becomes a type. Even Precious’ grandmother and abusive mother are under-developed in the novel.

Two people at the salon suggested that, despite any flaws they might have, financially successful books like Push might provide the industry with resources to support lesser-known literary achievements like Everett’s Erasure. Yet Erasure, published in 2001, has always been difficult to find, while Sapphire’s novel was prominent in bookstores and on every New York City street vendor’s table when it was published in 1997. This year, with the release of the film, Push was even easier to get online. Meanwhile, most folk had to borrow Erasure so they would have it in time to read before our salon.

Donna Grant, who has co-authored seven books with Virginia DeBerry, spoke movingly about the publishing industry. Grant said she liked Precious and added “I’m a fan of Push as well. But there are many engaging, thought-provoking stories that are not at the extremes.” Grant spoke from experience, and is able to bear witness to the experiences of other contemporary black women writers who have found it increasingly difficult to tell stories about black life that don’t express (or exploit) pathology or hyper-sexuality. At our salon, Grant asked what the awards for and marketing behind Precious really mean for other writers. If the gatekeepers in books and film only allow one type of African- American narrative to achieve critical and financial success like Sapphire’s, what does that say about our place in American society?

Lisa Cortes discussed the lack of diversity in American film. She said that “in 2009 there were two Tyler Perry movies and Precious—and that’s it.” Certainly, she said, more of our stories—more kinds of black stories—need to be told.

Filmmaker, author, and RingShout co-founder Bridgett Davis asked Cortes about her personal imprint on the film. Cortes spoke about creating a healthy and nurturing environment for lead actress Gabourey Sidibe on set. She also insisted Sidibe look attractive, with hair done neatly, onscreen. That led some at the salon to question the decision to cast Paula Patton as Blue Rain, Precious’ teacher, as she is described in the book as having long locks and a less tailored appearance. Cortes said Patton is an actress she and director Lee Daniels wanted to work with, and added that Patton’s image, because she is conventionally pretty, is a good one to resist stereotypes about what a black lesbian looks like.

Helen Mirren was originally on tap to play the social worker Mrs. Weiss, but was pulled into another project. Cortes spoke honestly about the decision to cast Mariah Carey in her role, because she brings her huge fan base with her, wanted to work on a serious project, and helps raise an interesting issue of racial ambiguity in the film.

Much of the criticism of Precious has focused on casting. Vassar film professor Mia Mask asked Cortes what she should say in response to her students who complained that darker-skinned characters are villains and lighter-skinned characters act as heroes or saviors in Precious. Mask started a student-faculty group on her campus last year that addresses issues of interest to people of color called The Forum on Race and (Popular) Culture. She had scheduled a late-semester meeting of this group, which members of the Vassar community across all racial lines attend, to discuss Precious, and she told the 40 or so people gathered on campus that, at the RingShout salon, “Cortes said the other young women in the film (at Each One, Teach One) were women of color and of various complexions and backgrounds. These characters were all helpful to Precious and positive figures in the story. Lisa [Cortes] reasoned that Precious had a variety of kinds of people in her life who were positive people of color.”

At Vassar, Mask said, “Even with these explanations, student and faculty reactions were mixed. Some were satisfied, many others were not. Folks were looking around the room rolling their eyes. One of my colleagues said he thought the filmmakers made a poor decision with these casting choices because they simply reinforced stereotypes. Several students agreed. A few scoffed at the idea that Mariah Carey added box office draw, given lack luster movies like Glitter. Then we moved on to discuss the abuse, [including] the way food was part of the abuse.”

At the RingShout salon, Southgate asked Cortes about the oversized bucket of fried chicken Precious steals in the movie—but is an individual portion, “a basket,” in the book. Of course food is generally associated with warm sustenance and the nurturing aspects of home life. In Push, however, food is a weapon used to abuse Precious. Cortes said she wanted to express the smells in Precious’ abusive household. She wanted the audience to sense how the apartment where Precious experiences so much pain feels—greasy and sticky to the touch. The oversized bucket of chicken symbolizes the abundant pain Precious endures.

Chicken as trope rooted in tired stereotypes, or chicken as familiar image used to present fresh ideas? Of course, each viewer must examine the art Cortes produced and interrogate not only the filmmaker’ s presentation of Precious’ life, but one’s own, personal response to the unrelenting abuse portrayed onscreen.

As awards season approaches, we only hope RingShout helped contribute to the public conversation around this challenging film. More discussions like ours and the one held at Vassar need to take place, and the RingShout Salon ToolKit can help you plan your own. Southgate, who opened her home for our event, said “I was pleased to find that the temperature of the discussion stayed reasonable, thoughtful and persuasive. I found my own hardened opinions, particularly about the novel, softening a bit. It was great to have such a diversity of views.”