Three Women Honor Their Sons by Educating Other Families About the Eternal Price of Police Brutality

Police brutality at the crossroads of the world – New York City – has become the focal point of a charged national discussion. Incidents of police shootings, excessive force, and deaths in custody have been reported from Florida to California, yet the cases that seem to draw the most media and spark the most searing family dramas have occurred in New York City’s ethnically isolated neighborhoods.

Amadou Diallo, Frankie Arzuega, Abner Louima, Yong Xin Huang and, most recently, Gidone Busch – a member of Brooklyn’s Hasidic community with mental illness shot 12 times after wielding a hammer in the street outside his home. After the deaths, aerosol memorials appear in Day-Glo colors on city walls. Eventually, life goes on for the victims’ neighbors. But for the families, particularly the mothers of slain New Yorkers Anthony Baez, Anthony Rosario, and Patrick Bailey, life will never be the same. In response to the shootings and chokeholds that killed their sons, these newly politicized women fight back with an organized quest for justice and safer communities.

Like most people, Iris Baez, Margarita Rosario, and Evadine Bailey know that there are good cops on the force. But it is the few who violate the sanctity of a community who drive these women’s search for justice.

r e c k o n i n g a n d r e m e m b r a n c e

Anthony Baez fell victim to a fatal police chokehold one evening in 1994, right outside his childhood home in the Bronx. In seeking retribution for her son’s death, Iris Baez stood, often crying but clear, always clear, in her quest for justice. Iris Baez’s strong presence is now a model of empowerment, and a source of inspiration for other victims’ families. She showed up at almost every public event where Mayor Rudolph Giuliani appeared, insisting that no one forget she had lost a son. Local media repeatedly broadcast her tearful demands for justice in the months following Anthony’s death. It was during that time that she received support from youth organizations such as the Latin Kings and the Zulu Nation. Eventually, police office Francix X. Livotti was convicted in federal court for violating Anthony’s civil rights. He received seven and a half years in prison, and Baez won a $3 million suit against the city.

But though she has “won,” Baez continues to advocate and mobilize. A foster mother who still runs the same active household where Anthony grew up, she founded the Anthony Baez Foundation, an organization dedicated to preventing police brutality by educating Black and Brown communities about the Constitution and their civil rights. In 1990, the Anthony Baez Foundation joined with the National Lawyers Guild and the Oct. 22 Coalition to Stop Police Brutality to create Stolen Lives, a book documenting the names and accounts of people killed by police all across the country. A second edition was released this fall, listing more than 2,000 victims of police brutality in 47 states and Washington, D.C., since 1990. More than half of the reported victims were under 30. “Young people are the generation most under the gun,” says Maze Hoffman, 29, an activist with the Oct. 22 Coalition. But while the cases tend to occur in cities, mostly striking young men of color, “police brutality happens in the suburbs and in rural areas” as well, says Hoffman.

The Oct. 22 Coalition is named for the first national day of protest against police brutality, held in 1996. Last year, participants dressed in all black to symbolize their solidarity with victims of police brutality. Events ranging from mass rallies to small group discussions to church plays took place in 60 communities nationwide.

s i s t e r s a n d m o t h e r s

But Baez’s efforts remain mostly local. Meeting other mothers, Baez says, “is like therapy for us. We talk about the courts, who goes where, what’s the next step. You need that support from another mother.” Genuine friendships have formed among some of these women, especially Baez and Margarita Rosario, with whom she co-founded Parents Against Police Brutality and recently shared a 1999 Women of Achievement Pacesetter Award.

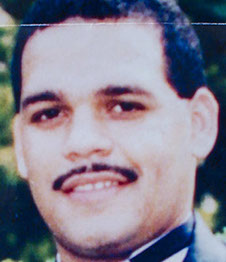

In 1995, Rosario’s son, Anthony, and nephew, Hilton Vega, were shot and killed in a hail of 22 bullets fired by police in the South Bronx. From their wounds, it was determined that all the bullets struck the high-school students in their backs and sides. Rosario says she formed Parents Against Police Brutality so “other people could be saved, so other families could learn.” It is a difficult battle. She strongly identifies with other victims. Perhaps the strongest statement of her alliance is the mural covering one side of her home, graced by the message of protest marches: “No Justice, No Peace.”

Rosario, an active member of the Congress for Puerto Rican Rights, keeps a tidy office in her home, much like Baez’s, where she devotes countless hours to her new mission: trying to insure that no more names are added to her wall of pain. While Rosario believes she gets her strength from God, her friendship with other mothers, especially Iris Baez, eases her personal pain. “We share a few tears,” she says. “We speak about the loving times with our sons.” But her alliances are about more than sorrow and memory. “It’s important for women to be a help to other women in our lives, so we can empower women.” Of her work with Parents Against Police Brutality, Rosario looks straight into the future and proclaims, “We’re gonna fight, and we’re gonna win.”

Evadine Bailey echoes this commitment. In 1997, her 22-year-old son, Patrick, was fatally shot in Brooklyn by a New York police officer. Just two years later, this same officer, Kenneth Boss, and three of his NYPD colleagues gunned down Amadou Diallo in the Bronx, and Bailey strongly identified with Diallo’s family. According to Bailey, who is charging the city with criminal negligent homicide, her son – like Diallo – had never committed a crime.

Another new activist-mother, Bailey reached out to Amadou Diallo’s mother. While fear among other New York mothers may subside with the passage of time, Bailey’s link with Diallo’s mother will never go away. When she first heard of Diallo’s murder, she says, “It was rough. I kept getting flashbacks of my son’s death – the pool of blood he was in. My son bleeding, bleeding, bleeding, bleeding. I knew then what [his mother] was feeling.”

By Eisa Nefertari Ulen, published in Horizon Magazine, January 2000