By Eisa Nefertari Ulen – Published in The Defenders Online, February 9th, 2010

By Eisa Nefertari Ulen – Published in The Defenders Online, February 9th, 2010

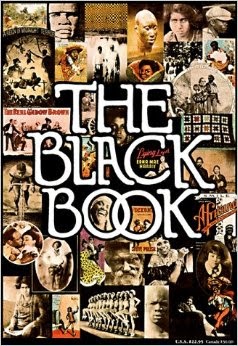

In the early 1970s, during the height of the Black Arts Movement, a group of scholars decided to document the African-American experience. They approached one of the few black women in book publishing back then, an editor at Random House named Toni Morrison. It was the right group, at the best time, teamed with a future Nobel Prize winner. Out of that moment and those folk—and their important mission—The Black Book was made.

In his introduction to The Black Book, Bill Cosby called it “a scrapbook…a folk journey of Black America…beautiful, haunting, curious, informative, and human,” and it is as intimate, revealing, heartbreaking, and uplifting as any treasured family album can be. This scrapbook, now reissued in a 35th anniversary edition, records the triumphs and tragedies of the African-American family.

The kin on these pages are our African cousins, our slave forebears. They are the uncle who, in 1898, became the fastest bicyclist in the world, and the uncle who, in 1911, was burned alive. The Black Book tells of the names Chango and Cuffe; it contains an ad for capture of runaways in Boston and models for black invention filed at the United States Patent Office in Washington D.C. It tells who we are because it remembers who we have been.

The Black Arts Movement of the 1960s – 1970s was, much like the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s and 1930s, a period of sustained artistic and intellectual production. Both movements coincided with a concurrent civil rights activism. The Harlem Renaissance was fueled by and helped power the Anti-Lynching Campaign led by Ida B Wells-Barnett and W.E.B. DuBois’ call for Uplift. A similarly symbiotic relationship existed between the Black Arts and Civil Rights / Black Power Movements. Likewise, during both time periods, a key aspect of the artistic imagination was occupied with documentation. Artists and scholars did the important work of recording the black experience in all its complexity and diversity – of telling our truths instead of letting others tell tales on us. This is the important work that gave us The Black Book.

For Morrison, who expressed her unmatched literary gift in the 1973 preface she wrote, The Black Book speaks: “Between my top and my bottom, my right and my left, I hold what I have seen, what I have done, and what I have thought. I am everything I have hated: labor without harvest; death without honor; life without land or law. I am a Black woman holding a white child in her arms singing to her own baby lying unattended in the grass…I am all the ways I have failed… I am all the ways I survived…I am all the things I have seen…And I am all the things I have ever loved…”

I remember buying The Black Book in yet another era, The Afrocentric 80s. That decade was also the beginning of The Crack Era, and by the early 1990s I was teaching elementary school in Baltimore, a city, like so many others, that was being torn apart by black-on-black violence. When I needed to show my young students who we really are, more than drug dealers and murder victims, more than the crack-addicted parents that some of my beautiful brown babies went home to each day, I turned to The Black Book. With it, and the stunning images collected there, I could let them see us—and their individual selves—as more.

Now, in 2010, we are in perhaps the twilight of what Kevin Powell called The Word Movement. This movement of Gen X artists and scholars was born during the Anti-Apartheid Movement and campaigns against police brutality. Just as the Renaissance had jazz and the Black Arts Period had Funk and Soul, we have Hip Hop. It is this continuum that has – and always will – see us through. It would be nice if a new Black Book would collect and record our experiences as a people from the mid-20th century to now, but the anniversary edition is not made weaker by the fact that it has not been added to.

This volume is more than a teaching tool. It is our shared family album, tracing us from the continent to the Carolinas, from cakewalks to hoe cakes, and it remembers everyone from Cinque to the KKK. Get it for yourself and get it for the people you love, the people who are also you.