By Eisa Nefertari Ulen, published in The Defenders Online, February 23rd, 2010

By Eisa Nefertari Ulen, published in The Defenders Online, February 23rd, 2010

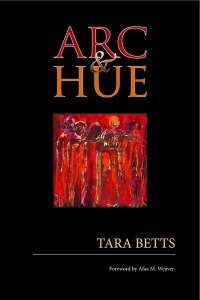

In her debut collection of poetry, Arc & Hue, Tara Betts articulates deeply-felt human emotion in a lyrical, beautiful way. Betts is a poet for the people. In her work, she celebrates the black female body, and rages against those who would assault it. She remembers the Civil Rights struggle, and offers a fresh perspective on the old issue of race. She creates a disturbing narrative of poverty that might just express more about class in a few lines of verse than an entire scholarly book ever could.

Betts is also a poet’s poet, and the work collected in Arc & Hue is often stunning. With a foreword from Afaa M. Weaver and blurbs from Thomas Sayers Ellis, Patricia Smith, and others, this debut collection feels very much like a launch into the canon.

Betts received her MFA from New England College. She also developed her craft as a fellow at the storied, celebrated home for black poets, Cave Canem. Her work has been published in a score of journals and anthologies, including Callaloo, Black Arts Quarterly, and Home Girls Make Some Noise!: Hip Hop Feminist Anthology. Betts, who teaches creative writing at Rutgers University, earned residencies from the Ragdale Foundation, Centrum, and Caldera, as well as an Illinois Arts Council Artist Fellowship.

In Arc & Hue, she has collected several poems that revere delicate life, including “Branching,” which honors Earth and ancestors as the speaker of the poem walks with her young nephew:

When he touches the trunk, he plucks

leaves as easily as tearing paper.

I stop his hand, tell him trees

may not walk or talk, but they breathe.

He yelps.

I inhale with a bittersweet smile,

take air I shared with my uncle

who resides where all trees go.

“Branching” reads like a prayer, a wish that all boys were just as gently and explicitly chided away from random acts that inflict pain. The poem “Understanding Tina Turner” is a sorrow song for a specific man who never was – and a shout for the redemptive soul force of the woman who escapes him:

Hurts twang the womb

Then escape into songs – like a man

Who never holds you too close, too long,

Trying to crush the music within.

Betts also expresses the power of psychological violence, and the violence of potent symbols that still hang from Southern trees. The speaker in “Jena, Louisiana” knows

“Noose turns epithet.

Slurs, a bread that rises

into red leap.”

“Jena, Louisiana” ends with the lines,

“We become new sum where

three times two is one.”

One people, one experience, one movement: The speaker seems to suggest that, no matter what, victory will be won.

In “Sestina for the Sin,” Betts crafts a powerful poem that reveals the many acts of injustice that mob violence enables:

“Picking through the bones becomes part of the sin.

This is what happens at a lynching.

This is what happens when you are dark.”

This is a poem that remembers.

In the narrative poem “For Those Who Need a True Story,” the speaker tells a vivid tale of a boy named Raymond, his mother, and their landlord, who deducts $12 from the rent for every rat the family kills. This “true story” is haunting, the rats are like ghosts, very real, very alive, then very dead, and poverty is the stench of their corpses, “the smell of poison rotting from the inside out, / the scratching inside the walls at night.”

Betts has also included poems that are witty, erudite, and fun. Her “A Survey on Enjoying Verse” should be required reading for every emerging poet who was ever “asked to purchase titles that have not been spellchecked” or believes “Reading other poets might influence my work” or “used my money to buy the latest urban classic PimpHand: Smack Them Hoes Wit Love.”

Betts plays the dozens, using her sparkling gift for verbal dexterity in “Proverbs from the Pulpit of Rev. George Clinton” with funkadelic aphorisms that wisely intone:

Yea, though I walk through the shadow

Of poverty, I seek the boogie in the booty.

The a** always follows the mind.

If you read Arc & Hue, I promise: Your mind will surely follow.