America hates her children.

America hates her children.

How else can we explain inequities in school funding, the high rate of homeless children, and infant mortality rates that rival those of the developing world in this, the richest country on earth?

America is really kind of sick. We coo and ooh all over little ones in formula ads but deny women the dignity to breastfeed in public without shame, confining mothers to closets and huddling babies under blankets, blaming them even in infancy just because they want to eat the best thing in the world — milk from their own mammas. It is an evil trick: to parade children around, to raise and spin them in television commercials, to motivate them to succeed, and then, in a most sinister way, deny them the education — as well as the housing, the health care, the food, even — that they need to do well. Perhaps this is why Jordan Peele’s journey to the depths of the American psyche begins with the seemingly nonsensical, backwards steps of a child.

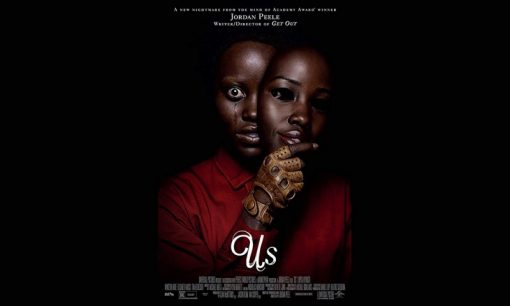

Jordan Peele’s Us begins in the dark night of summer 1986. Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing begins on a scorching hot morning in 1989. Lee ranks among the top American filmmakers of all time, and Us solidifies Jordan’s place as Lee’s auteurist peer. These parallels aren’t the only ties between the two. Lee’s film is set in an austere streetscape not far from East Coast communities like Howard Beach, while Peele’s is set in the leafy suburbia of a West Coast seaside town. Each is a microcosm for examining the polarizing tensions that grip Americans, that bring out our worst selves. When it was released in theaters in 1989, Lee’s film compelled a critical self-assessment, an honest reckoning with how close our daily interactions with the Other teeter on the edge of chaotic fury, and launched a national discourse on American racism. Peele’s play on language in the film’s title — Us/US/us — signals that the film is a similar commentary on “Americans.” Both filmmakers have plunged into the depths of the American unconscious to create art that is striking, bold, and terrifying.

In Do the Right Thing, a neighborhood is altered forever as emotions shift through Freud’s three levels of awareness, from the conscious, to the subconscious, to the depths of the collective unconscious. Understanding these shifts is key to understanding Us.

At the conscious level in Do the Right Thing — the level of awareness — characters of various ethnic and racial groups spew obscenities about people of other ethnic and racial groups. The epithets remain conscious, whispered, muttered under characters’ breaths, under control until, in one breathtakingly confrontational montage, characters surface their hateful desire to attack the Other from the subconscious and, without consciously thinking, fire directly into the camera — at us, the audience, and at the United States, at US. The montage shocks and awes because characters bellow from the subconscious and rampage out of control. The heat of summer animates a searing rage no popped fire hydrant can extinguish.

This montage also foreshadows the incineration of a neighborhood pizzeria named Sal’s.

Neighbors in this tight-knit community have assigned local teens with nicknames with Dickensian, on the nose meaning, and all of these young people eat pizza at Sal’s. Buggin’ Out, irritates Sal when he asks “why there are no Black people on the wall.” Radio Raheem needles Sal when he blasts Public Enemy’s “Fight the Power” in the restaurant. Separately, these neighborhood characters provoke Sal’s ire; together, in a clashing soundscape, Buggin’ Out’s roaring demand for representation and Radio Raheem’s booming demand for equality arouse in Sal a subconscious need to reestablish the hierarchy of power that privileges his whiteness. Sal whacks Raheem’s radio with a baseball bat, weaponizing the phallic symbol of America’s favorite pastime. After a police officer grips his own phallic weapon, his nightstick, and fulfills Sal’s subconscious desire to silence Radio Raheem forever (like so many other People of Color killed by police), the entire neighborhood shrieks, cries, mourns into the screaming night. Ancestral memory surfaces, and then burns.

The next morning, Sal is left to stare and wonder at the hollowed, dark, dripping symbol of his deepest unconscious desire, which was, counterintuitively, to do the very thing the community did: destroy the pizzeria.

Lee’s 1980s Brooklyn is a community Sal consciously said he loved but subconsciously hated. He hated that he had to drag his sons to Bed-Stuy to make a subversion of Italian cuisine to serve Black people. Sal’s surface-level, conscious love helped him cool his roiling, repressed subconscious hate. Below that subconscious hate, in the well of his unconscious, Sal always wanted to destroy the thing that connects him to the Black community. Deep down, Sal hated Sal’s.

That’s why there were no Black people on the wall.

Like Lee, Peele plumbs the deep recesses of the country’s collective unconscious. It makes perfect sense that, in the opening sequence of the film, a young Black girl takes the first steps down: steps into a hall of mirrors that, weirdly, faces not the boardwalk but the sea. It is to the sea that the Black girl first walks, until a strike of cloud-illuminating lightening causes her to turn and enter the hall of mirrors.

Carl Jung, an early supporter of Freud, identified water as a symbol of the unconscious, a tricky little layer of the psyche that is automatic, of which we are largely unaware, and is often tethered to anxiety, fear, worry. The sea is the collective unconscious in Us. It is the symbol of memories — many, horrible memories, formed over centuries of racial violence and oppression in the US, in us.

For Peele’s characters, the unconscious is visible in habitual impulses made more striking when these same gestures are mirrored by the red-clothed “us” — the characters’ mysterious, sinister counterparts that dwell beyond and below the funhouse mirrors. Gabe, the father of the film’s central Black family, has a habit of pushing his glasses up his nose when he’s nervous. This is suddenly made prominent when his twin awkwardly grasps Gabe’s glasses and learns to manipulate them himself. Gabe’s habit emphasizes the fact that he is always the last to see what is really going on in every crucial scene. Gabe’s conscious terror is that he cannot protect his family — a terror shared by centuries of Black men who could not protect their families from the terrors of the US. His unconscious desire is fulfilled when he no longer has to look out for his family: he tells his daughter that his wife is the one who knows what to do, and then, in the last scene of the film, not only gives up the driver’s seat of the vehicle they’re riding in, but also moves to the back seat, so that he no longer has to see what dangers they might be getting into next.

Zora, Gabe’s daughter, masks centuries of Black female pain with a nearly-permanent, stoic facial expression. Black women have long been witnesses to strong women raped, children sold away, angry husbands roasted and flayed. Ancestral memories intersect in Zora’s unconscious mind, denying her the privilege to turn cartwheels on the beach like her white counterparts or feel free enough to run with wild abandon on the track team. While Zora fixes her face into a placid calm that helps her — like all Black women — instinctually keep it together, her doppelganger glowers. Named for the writer who gave us the gift of a truly free Black woman protagonist in the novel Their Eyes Were Watching God, Zora has no release from her conflicting, unconscious urge to express her authentic self. An adolescent daughter clenched between girlhood and womanhood, Zora’s twin expresses Zora’s submerged rage, switches to a frenzied glee, then remains caught, red-robed and loopy, in a trippy trap between the two. Zora’s twin giggles eerily, even when her body is contorted into a macabre ruin. Zora’s twin is the Black female body, hanging like strange fruit, crowing at the literal manifestation of her social position through time.

Jason, Zora’s younger brother, avoids social interactions and pulls on a child’s Halloween mask to cover his face when he is nervous. Meanwhile, his twin’s entire head is covered in a bondage prop worn by submissives. Both boys unmask when they huddle in Jason’s closet hideaway. There, twin Jason reveals self-inflicted burn scars that silence him to mere grunts. But these burns also protect Jason from his conscious fear of social interaction and emphasize his unconscious desire to disappear. Jason’s most wicked unconscious desire, to self-immolate, is fulfilled when he backs his twin into a rage of flames. This act does not, however, free him from his mask.

Adelaide was badly damaged when, as a girl, she was dragged through the awful unconscious of the US. Yet, all conscious African American mothers have to drag their beautiful Black boys to that same place when they painfully recite The Talk. To tell Black children to submit to police power in order to survive the encounter, to live and be Black another day, is to tell them the narrative of our occupation, of the fetishistic desire to penetrate and destroy our bodies with bullets and batons. Always, every time, The Talk has to be told to precious sons far too young to have to know such terror. The shock of Jason’s submersion in the unconscious of the US traumatizes him. This trauma is explicit on his face. He stares at Adelaide as she drives, searching for psychological release. There is nothing she can do. It is what it is. Her non-verbal shrug communicates a kind of sublimation, gives him a “boy you’ll be all right.” So he pulls the mask down one last time, and this final gesture is one of the most haunting moments in the film.

For these middle class African Americans, unconscious, habitual behavior shields, veils, protects the authentic self that dwells beneath the mask. Their red-cloaked twins remove those masks. Peele’s film suggests that, for Africans in the US, habitual behaviors roil out of the reservoir of ancestral memories, painful memories, as vast as the sea when seen from the shore, as sudden and scary as a storm.

The beachside carnival that anchors Us is an all-American boardwalk. These arcades exist along every coast. As the movie begins, the Black girl, following her inebriated father and his long-suffering wife, gazes at her parents and their pattern of behavior, a pattern that, even in her youth, is as familiar as the centuries are long. Is Father a real man? Can he throw the ball or whack a mole to win a prize for her? Is Mother too harsh, too demanding, when she asks him to keep an eye on their only child so she can relieve herself in the bathroom? What will become of the two of them, her parents? And what will become of her?

As Young Adelaide follows and gazes at them, she also observes the wild, frenetic fun all around her. Everyone else is white. They scream on the roller coaster, feed each other what hardly resembles actual food with their hands, nearly like the animals they once were. They play rock–paper–scissors and shoot at targets. People rage on the rides, because the carnival is the place where you can let out your urge to scream. The carnival is a scream. But the Black girl is nearly silent. The unconscious is visible all around her. Beneath the frivolity and fun, she sees the menacing, frightening glare. She needs to escape.

In 1986, the country literally linked, hand to hand, in a most hypocritical display of absurdism. The bizarre performance art Hands Across America — mocked endlessly in Us — revealed the tension between America’s human desire to seek meaning and purpose, and the chaotic reality of hunger in America. This hunger was so horrific under the Reagan-Bush trickle-down policy that the government had taken to giving out blocks of cheese to compensate for lack of access to jobs and food. This hunger started just five years earlier, when Reagan cut $1 billion in federal funding for school lunches, reducing a kindergartener’s daily meal allotment to half a slice of bread, four ounces of milk, half a cup of fruit or vegetables, and one ounce of meat, which is about a quarter of a medium hamburger. It was the year the president of the United States said, for children who depend on free or reduced lunch to survive, ketchup counted as a vegetable.

That’s how bad it was.

Young Adelaide’s family is middle class. They own a summer home in a white, seaside community. She carries a candy apple. But her parents also carry the invisible burden of centuries of submersion in the unconscious, collective chaos of this country. Father needs a drink, needs a smoke. Mother can barely contain her disappointment, her disdain for him apparent in her eyes, her neck, her tone. And yet, she stays beside her man, almost imperceptibly twitching at his side.

The 1980s — the formative years of Generation X — mark the nation at a crossroads. For African Americans, Gen X is the first generation to inherit the privilege of access. Though denied equitable inclusion because of persistent de facto segregation, Black Gen Xers are the first to be born and raised without “whites-only” signs, without white mobs slicing into their necks, without white hands abnegating their humanity with iron chains. Black Gen Xers gave the nation the first commander-in-chief of African descent, the first Black billionaires. And yet…

The Wilson family is still the only non-White family in this seaside town. Black Americans are still relegated to intense segregation, still live in terror of white cops burning bullets into children’s chests, still disproportionally caged and dehumanized in for-profit prisons. That we still have the first Black this and the first Black that after 400 years is absurd and surreal. A sizeable Black middle class is finally growing, but doing so just as the white middle class is becoming a memory.

Meanwhile, the ice caps are melting, mass murders take place with increasing regularity, and, of course, Trump. The whole nation is at a crossroads. We will either utilize renewables or die, get rid of the guns or die, elect a sane president or die. Sometimes it feels like we are on the brink of new Civil War. We are at war with ourselves.

America is a horror.

No wonder two of the best filmmakers, free to be in their beautiful Blackness, have produced meditations on America that have already made cinematic history. Spike Lee explicitly says his film is about Black life, and yet Do the Right Thing is just as much about white life and the psychology of whiteness. Jordan Peele explicitly says Us is not about race, and yet it is a narrative that could only be told by a Black man in America, one who, as W. E. B. Du Bois wrote “ever feels his two-ness.”

Us is about our double consciousness, our subconscious, and our collective unconscious, too. As Adelaide’s interminable descent at the end of Peele’s film makes clear, Us is about the American unconscious, about the terror, the horror, deep down inside us, all of us in the US. Our memory, our collective unconscious, is African children stolen from their mothers, Indigenous children stolen from their mothers, and now South American children stolen from their mothers. We have always stolen children from their mothers.

And so the red-cloaked mimicry of that pathetic Hands Across America exercise is not a result of everyone going deep down, as Adelaide does to confront the conscious self she switched places with. The red-cloaked versions of us have systematically and methodically — habitually — practiced and planned their escape. The place where the unconscious lives in Us is a barracks-like, institutional-looking space. In this dismal place, where the unconscious us dwells, the twins have plotted a bloody, scissors-wielding riot.

At the conscious level, we are the humanity of Hands Across America, but our collective unconscious is the terror of Thriller Night. Both shirts fit. Our consciousness tells us we are joining together to save one another, but in our collective unconscious America is a cackling riot, a violent rage. Who is that ghoul, the audience of Us asks, applying lipstick in the mirror? By the end of Peele’s extraordinary film, it is clear that the self-mutilating specter in the mirror is us, “Americans!” The only escape? Led by an unmasked Black woman, who knows better than anyone the truth of America’s unconscious desires, the goal is to survive the night. The sunlit path to freedom is not north but south, skimming along the coast to cross a new border.

By Eisa Nefertari Ulen – Published in the LA Review of Books, 04/25/2019