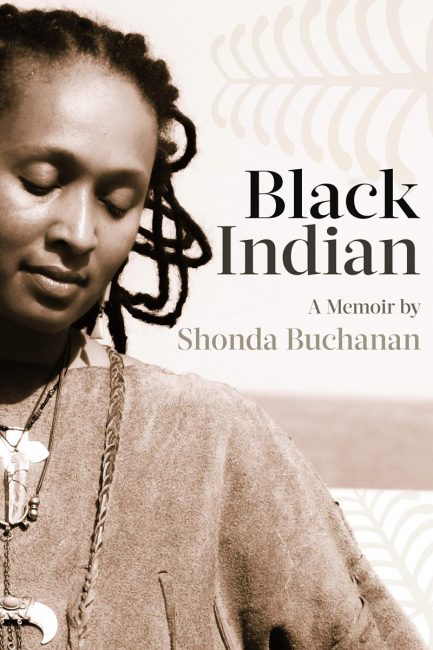

Award-winning poet Shonda Buchanan honors multiple literary traditions in her breathtaking new memoir, Black Indian.

Award-winning poet Shonda Buchanan honors multiple literary traditions in her breathtaking new memoir, Black Indian.

An educator, freelance writer, and literary editor, Buchanan is a culture worker with deep, decades-long engagement in communities of color. Her work honors the complexity and diversity of these Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) communities. At once Indigenous, Black Female, Speculative, Feminist, Womanist, Urban, Southern Gothic, and counter to the Tragic Mulatto stereotype in American literature, stage, and film, Black Indian is a quintessentially American narrative.

Even descriptions of decay and violence sing with Buchanan’s poetic voice. In her mother’s city home, “[t]he thin brown carpet is worn down to the color of a deer’s trail” in the woods. Her aunt, like one out of three Native American women and 20 percent of Black women, is raped, and “her body was a scar, because she’d been ripped open like a pig hanging from a spit on a tree.”

Funerals bookend this narrative; the characters, Shonda’s mother, fathers, aunties, grandfather, siblings, and cousins, curse their way through each family gathering. Shonda’s family, the subject of this stunning memoir, is wild. Uninhibited and crass, they cuss, fight, and fumble more often than they catch the ball.

The first funeral, tense, quiet, eerie, sets up the conflict at the heart of the book. This family is in crisis, divided and faltering, unable to touch, even, in ways that suggest warm belonging. This hollowed-out family, Buchanan explicitly asserts, is the result of cultural theft. Buchanan says she resents her “grandfather’s weak, bitter struggle with manhood. His un-knowledge of our past. He was a lousy farmer. He was a horrible father and husband. He beat my mother. He had no memory of what we called the Red Road, no African spirituality of the Orishas of West Africa. Our family was ritual-less: we practiced the ritual of violence.”

By the time the second funeral occurs, the distance the memoirist craves from kin has offered her opportunities for recovery. Buchanan reclaims her Indigenous identity, and the rituals associated with her people. Similarly, she has actively engaged the reclamation of her African self. Though her ancestors were stolen, over centuries and via various iterations of dispossession, Buchanan does, indeed, become found, secure in her dual heritage and liberated by the cultures that formed her.

The sweat lodge figures as prominently as Buchanan’s loc’d hair in this fully realized assertion of her authentic self. Buchanan ritualizes care of her beautiful brown body, liberating herself from a history where pencil erasure, blood quantum, enslavement, and segregation conspire in a centuries-old abnegation of her ancestors’ full personhood. Forced into multiple racial boxes even across the span of one lifetime, Buchanan’s ancestors disrupt the black-white binary. A spectrum of skin shades, hair textures, and freckle patterns resist the tension in this binary and explode its inherent contradiction, the binary’s inherent lie, that there is no middle.

Two-ness haunts Buchanan’s people. But these Mixed folks are not inherently tragic because they can’t make themselves fit in; the tragedy is that they are cast out. Like Black Indian tribes the state refuses to acknowledge but who retain their traditions and so legitimize themselves, Buchanan recovers a certain wholeness as she centers her people and resists the systems of control that would slice them into two oppositional, unknowable, fetishized strangers. “My family records for ‘Race’ include Colored, Mulatto, Multiracial, White, Delaware Pequot Indian, Cherokee Indian born in Oklahoma, Freeman, Black,” she says. So many ways to describe, to classify, one American family.

Buchanan remembers and tells

those who first came on the boat from Africa in the 1500s and escaped to an Indian village, married into the community, and made beautiful Mixed babies. Those 1600s Indian slaves and indentured servant women who slipped back away into the night with their new Black African husbands, purchased to marry after their men folk had been killed or imprisoned in the French Indian wars, and they made beautiful Mixed babies. Those Maroons, those Mulattoes, those slaves, those shiners, those coopers and livery men and blacksmiths; those survivors. Yet no consistent records of their lives exist. My life is their unrecorded testament, the proof […] their Mixed blood stories live in me.

For women writers of color, 2019 is a year of revelation, of amplification where there has been an unyielding hush. Bridgett Davis’s gorgeous memoir published earlier this year, The World According to Fannie Davis, celebrates the middle-class respectability of a mother who enriches her family as one of the very few women booking The Numbers, the underground, illegal lottery run in Detroit during the Motown Era. In Black Indian, Buchanan’s mother maintains middle-class status by a macabre twist of fate — yet another death that offers her a different kind of triumph, not over poverty, but over abuse, family addiction, and a feeling of abandonment. Both books trace migrations: Davis’s family’s along the Great Migration and Buchanan’s family’s along the Trail of Tears.

While the Great Migration was an exodus of African Americans from the terror and dispossession of the South, Davis’s Southern grandparents were land-owning and stable, one of the lucky Black families to hold on to their property despite the ravages of predatory Klansman throughout the region. Buchanan’s grandfather also holds on to a farm, but does so in the Midwest, where the Michigan soil seems to cultivate in him resentments so deep and unfocused, his children and their children suffer the fury of his inherited, intergenerational trauma. Both Davis’s and Buchanan’s memoirs share yet another interesting theme: the revelation of family secrets. Davis unveils the truth of her mother’s occupation, that she was a number runner in Detroit. Buchanan unveils the truth of her mother’s rape, the truth of her mother’s abuse, the truth of her mother’s troubles.

I first met Buchanan many years ago, at the National Black Writers Conference, a biennial event run by the Center for Black Literature at Medgar Evers College that has attracted luminaries like Toni Morrison, Cornel West, Rita Dove, Edwidge Danticat, and Sonia Sanchez (and which also funds an elder writers workshop for African Americans that I facilitate in Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn). There was Buchanan, listening, growing her community of writer friends, peering into the eyes of each person she spoke to, connecting. She and I have not kept in regular communication over the years, but I was always happy to hear of her accomplishments, well-deserved awards, and publications. What I never knew, was that this sister who was “working on a book” was crafting such an arresting, haunting tale of forced displacement and its effects on one prototypical American family. That even when she was not at a conference, she was still making healing, affirming connections for us all with each line of prose.

By Eisa Nefertari Ulen – Published on LA Review of Books, November 6, 2019