Published on LAReviewOfBooks.org –

Published on LAReviewOfBooks.org –

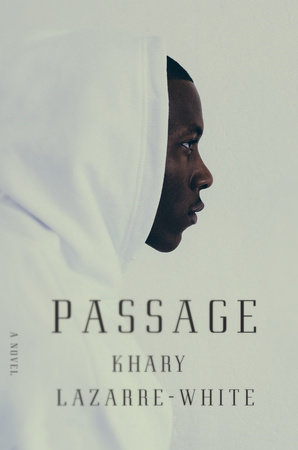

The Space in Between: Afro-Surreal Liminality in Khary Lazarre-White’s “Passage”

By Eisa Nefertari Ulen | November 18, 2017

TO BE Black in the United States is to be in a perpetual state of liminality.

This space in-between is one that occupies us as much as we occupy it; meaning, to be Black in the United States is to experience a perpetual state of Du Boisian twoness, to wear Dunbar’s mask, just to survive. Witness: The most patriotic act in a time of crisis, to engage our participatory democracy through First Amendment political protest, is condemned by the occupant of the highest office in the land, while adherents to 156-year-old symbols of treasonous secession are condoned by the same president.

Khary Lazarre-White’s debut novel does not center athletes who take a knee during the national anthem or neo-Nazis who take to the streets with tiki torches. Passage is set in 1993, decades before these recent events. But to be Black in the United States is to know there is no such thing as time. Even 156 years is not long enough to count the sustained violence against Black bodies, as the passage from the first cries for return to Africa to the rallying cry that Black Lives Matter is 398 years long, and we are still counting. All this time we spend adrift in American society, yearning, advocating, kneeling, for equity and inclusion. We are centered by the bright lights that broadcast our pain, but marginalized by voices insisting we haven’t been injured. We are kicked down and then blamed for being so low. This Afro-Surreal experience is a constant tension in the Black experience and in Lazarre-White’s book.

The entire landscape of Lazarre-White’s Passage is Afro-Surreal, with howling wolves that pursue Warrior, the male protagonist, and a demonic, deranged giant who commands them. Ancestors emerge in stunning clarity to interrogate Warrior, to demand, really, that he bear witness to their lives, that he remember them, and tell their stories. Spiritual entities, both evil and benign, surface in this urban dystopia, but their presence is not speculative or magical. Spirit is felt, not imagined. Spirit is present, not distant. Spirit is not hallucinatory. Spirit is real.

The torment of the Crack Era is also real. In Warrior’s 1993 Harlem, police brutalize Black children, an addict trades her daughter for one more hit, and three men rape a woman on a snow-swept rooftop while a demonstration against oppression fuels righteous anger in the streets below. At times it feels like too much. The reader wants to break free from the madness that circumscribes Warrior’s world — and this is the point. A high school student whose intellect goes unnoticed, Warrior cannot close a book to escape the maelstrom, and neither should the reader. After all, if certain scenes are difficult to read, Lazarre-White implies, imagine how difficult it must be to live them.

This dystopia is his neighborhood. With so much chaos all around, even the simple act of Warrior getting dressed or building a snowman with his little sister elicits tension in the reader. But all is not bleak, screaming pain. Kinetic, even frenzied scenes are counterbalanced by the serene power of Warrior and his family. He contains all this energy, remaining stoic, even still, bolstered by the calming warmth of his mother’s touch on one side and the rhythms of his jazz musician father’s bass on the other.

Warrior’s divorced parents live in different boroughs, but in their commitment to their children they are intimate. Family, Black family, preserves the past and ensures the future despite the unwillingness of social systems to support their efforts. Warrior’s family perseveres despite social services — not because of them.

Warrior’s mother is a teacher who agonizes over the students who “sit in the back of the class every day, looking just as mad and surly as can be.” Her son is similarly sulky when he enters the school he attends. Warrior is haunted, and afraid. He is also vulnerable to the predatory assault of police, called soldiers, each time he leaves his home. Actively listening to her son enables Warrior’s mother to maintain an edifying presence even when they are apart. She works in community, ensuring to the best of her ability that the young people in it, young people who look like her son, and the young person who is her son, will survive to step into the future.

Back in Brooklyn, Warrior’s father preserves the past, sorting and archiving the family tree, old diaries, “registration papers that had been pulled from the records of the Freedman’s Bureau decades ago,” and deeds to land “lost in late night card games played by the light of kerosene lamps, at tables filled with too much moonshine and too little sense, and in agreements signed by the force of burning crosses and creaking ropes.”

Warrior’s mother’s fear, that she might lose children, even her own child, and so lose the opportunity to secure their tomorrow, is the author’s own, and Warrior’s father’s passion for the past also belongs to the author.

Lazarre-White co-founded The Brotherhood/Sister Sol, an award-winning, Harlem-based organization that provides youth leadership training, social justice, and African and Latino history. Recovering children from the harsh, artificial lights of police sirens and hospital rooms that would dim young people’s inherent and brilliant power is an act of resistance consistent with the trick question posed by a park-dwelling character nicknamed Weatherman in Lazarre-White’s book: “[W]ho stole the sun?” Weatherman repeatedly asks Warrior, referring to the Middle Passage that figures so prominently in the work of African-descended writers throughout the Western Hemisphere, while signifyin’ with verbal dexterity in his use of the pun on son.

Weatherman also references Plato’s sun as a symbol of knowledge, truth, and critical self-awareness in the Western literary tradition. Enabling children with the tools and skills necessary to realign their beautiful Black selves is a mandate at Bro/Sis. Passage is set just two years before this Harlem institution’s founding, suggesting that the realities described in the book inspired the intentional focus Lazarre-White required to begin to build Bro/Sis back when he was still an undergraduate at Brown.

Lazarre-White seems intent on continuing Bro/Sis’s mission, to reach and recover YA-aged readers, with Passage. He has crafted the novel to appeal to both young people and the adults intent on understanding and anchoring them. Take note when Warrior explains his disdain for those who believe a mere shift in personal attitude can effect substantive change:

Do you know how insulting it is when people look at me and ask, “Why don’t you smile more?” The ignorance of their question only makes me grow colder, and I always respond, “Why don’t you open your eyes?”

The idea that anything short of shifts in policy will bring effective change to ravaged communities is ludicrous to this young person. The concomitant implication in Warrior’s statement is that blaming children for their own disenfranchisement by enforcing the politics of respectability is just another way of denigrating Black and Brown youth.

Warrior speaks with “his true voice,” what the author also calls his “his poetry,” but his is not the language of average American teenagers. Warrior’s gravitas derives from his family and his spiritual connection to the past. He code-switches in yet another iteration of verbal dexterity, or signifyin’, in the novel. Though his more professorial passages may sound inauthentic to some readers, listen to him, and take notes, as he instructs, and consider the charge driving writers of color in this country and globally. It is two-pronged.

On one side, African-descended writers produce art, and this is very much in the European tradition of l’art pour l’art. The narrative should be beautiful, and this beauty is surely enough for it to exist. However, in African ontology, art is also utilitarian; it does something. The drum communicates, a garment signifies status, a facial mark reinforces interdependence in community, a dance initiates one’s own womanhood.

In African ontology, art works. Art acts. And so among writers of color the story must tell. It must speak for a singular experience inhabited by one main character, and also for the nameless, countless living, breathing, bleeding, laughing, surviving African-descended people who crossed over the passage, who cross centuries, who cross continents. Warriors live, have lived for hundreds of years, and will keep on living, in Baltimore, in Brazil, on the forgotten island of Barbuda.

The overwhelming scope of our dispossession is surreal, and so Black writers must make beautiful narratives that repossess. It is an ambitious literary project that Black people count on, as we are still counting. In the final scenes of the novel, Warrior occupies the streets. The streets occupy him. The beautiful struggle, in Passage, is to bring all Warriors back home.

Published on LAReviewOfBooks.org by Eisa Nefertari Ulen, November 18, 2017.