This review first posted on Truthout.

This review first posted on Truthout.

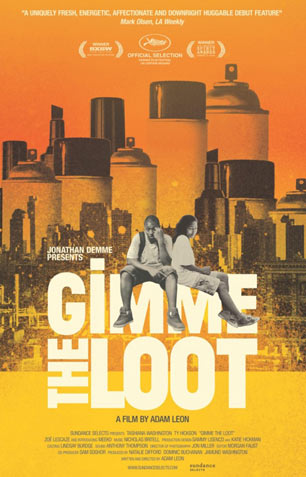

Film “Gimme the Loot” Pays Homage to the Graf Writers Who Risk It All

Saturday, 29 June 2013 00:00

By Eisa Nefertari Ulen, Truthout | Movie Review

Women graffiti writers never gained widespread prominence in hip hop the way women MCs did. While people around the world recognize the names of vocal artists from MC Lyte to Lauryn Hill, few people, even hip hop heads who live in the United States, can name graf artists like Sandra “Lady Pink” Fabara or Gloria “Lady Heart” Williams. The patriarchy and racism that structures American society infused hip hop with a sexism that denigrated black women culture workers, including breakdancers and D.J.s as well as graf artists, denying all but the most popular lyricists a place in the mainstream, while forcing female taggers, and their talent, to the margins.

An award-winning film that opened to limited theatrical release on March 22 examines a day in the life of one woman artist in this male-dominated culture, along with the male partner with whom she schemes to “bomb the apple” in Queens, New York’s Shea Stadium. Gimme the Loot stars Tashiana Washington as Sofia, a young woman from the Bronx whose quiet beauty and stunning talent often charms, and sometimes threatens, the many men who dominate the subculture she inhabits.

With her partner Malcolm, played by Ty Hickson, Sofia decides to do what no graffiti writer has ever done: spray paint the apple that rises like magic at Shea every time a Mets player hits a home run. Plagued by a rival Queens crew that tags their work up in the Bronx where Sofia and Malcolm live, the partners seek to shame their adversaries by bombing this symbol of their borough’s pride for “everyone to see.”

With playful nods to flip-flop-wearing gentrifiers (made especially funny when one character runs the city in his socks through much of the film) and the blasphemy of renaming a hometown stadium after a multinational corporation (the ultimate tag), Gimme the Loot is a smart film. Winner of a South by Southwest/SXSW Competition Award and an Independent Spirit Someone to Watch Award, first-time director Adam Leon merged his own professional backgrounds in both art and film to pay homage to the writers who risk everything to share their work, for free, in the public realm.

In the opening sequence, set in the 1980s, a woman with big hair and chunky gold holds her own with two men who openly boast on a local public access cable station of their plans to bomb the apple. Later in the film, and 30 years later in real time, three graf artists wear masks as they talk about their work for digital upload to a web site. These scenes anchor the film – and not just by placing Sofia and Malcolm’s quest in historical context through the use of actual 1980s footage.

Former New York mayor Ed Koch demonized public artists with his use of dogs and razor wire to protect subway yards in his 1980s War on Graffiti, a war he only half-jokingly said he would rather wage using wild wolves instead of trained dogs. During Koch’s reign, Michael Stewart died while in police custody after tagging a subway station in the East Village. Thirty years later, graf artists have to mask their identities to continue to work. Sofia and Malcolm’s world is dangerous, with criminality inherent in the work they do, and constant harassment in the streets where their work is done.

Despite their anonymity, indeed, their invisibility as they move through New York City while desperately trying to scheme the $500 they need to pay the guy who has agreed to sneak them into Shea, everyone in the world of graffiti art knows Sofia. But her renown, unfortunately, offers her few benefits and mo’ problems.

A day after she struggles across a rooftop to bomb a wall with her art, the Queens crew has tagged it with the B-word. At one point in the film, the boys from Queens even tag her, holding her down Tawana Brawley style to initial her T-shirt. But Sofia can’t be held down for long. Indeed, she holds her own. As she gazes at her ruined art, Sofia channels her anger into a resolute conviction to bomb Shea. While four young men restrain her body, she manages to spit an emasculating dis at the boy who scrawls his tag across her chest. A soul survivor in the city, Sofia consistently fires with the same quick-tongued fierceness glimpsed in the 1980s cable access queen, who acts as a cultural mother that has bequeathed her power to Sofia from the film within the film Leon employs.

Sofia even looks more like a woman from the golden age of hip hop. Clad in baggy shorts and a loose shirt that she turns inside out when she is tagged, Sofia is desirable without obviously displaying her sexuality. She is a sharp contrast to the video vixen who has sadly become the predominant image of women in hip hop.

Instead of gyrating in some man’s tricked out car, Sofia rides her own bike. Instead of swinging a weave that hangs to her behind, Sofia pushes flyaway wisps of hair back into a loose bun. Instead of working a pole to compel men to give her money, she strategizes with men about ways to get it for herself. When she is cheated out of money she hustled hard to earn, she slaps back using a sticker emblazoned with her tag in a satisfying act of defiance. While two men openly express their romantic interest in her to each other, Sofia is busy, literally stacking paper to gain access to Shea and generate work that would rise above the boys who work so hard to put her down.

In her world, men hyper-sexualize her, scrawl on her, rob her, even physically assault her, but Sofia resists, triumphantly, gracefully and consistently.

Gimme the Loot is not a perfect film. The narrative never gives the audience insight to Sofia’s home life. We glimpse Malcolm’s home, know he has a mother, linger on images that suggest a stability that, perhaps, empowers him to boldly write his name all over the city. Sofia gets none of this.

At one point, Malcolm suggests that bombing the apple might offer Sofia escape – but we never learn what she would escape from. This problem of black characters who lack family in American film is a persistent one, and Gimme the Loot would be stronger if Sofia’s personal story, her motivation to go through so much just to spray her name on a wall, were stronger. Or even just there.

Despite this flaw in the development of Sofia’s character, Leon has created an important film, one that centers a female street artist, a black woman who moves from the margins, a space we sisters like Sofia occupy every day, even in movies that focus on our culture.

1980s-era classics like Beat Street, Breakin’, and even Wild Style situated men in lead roles. Through the 90s Boyz n the Hood era, only Set it Off told the story of women seeking escape from the circumscribed borders locking them in a state of dispossession. Like a young Kerry Washington in the 2000 indie film Our Song or a young Irene Cara in the 1976 hit Sparkle, Tashiana Washington’s performance is a gift – but in Gimme the Loot, instead of song, this sister expresses herself with the whirls of color she sprays.