Published on HuffPost.com –

Young Lakota Activist Campaigns To Make Plan B Available, Affordable To Native Women

By Eisa Ulen | September 19, 2012

Sunny Clifford, a 26-year-old Pine Ridge Tribal park ranger, has launched a Change.org petition that seeks to improve the quality of women’s lives by making Plan B available—and affordable—throughout Indian Country.

Just months after the Native American Women’s Health Education Resource Center (NAWHERC) published a startling February 2012 report documenting legal rights violations across Indian Country, “Indigenous Women’s Dialogue: Roundtable Report on the Accessibility of Plan B as an Over the Counter (OTC) Within Indian Health Service,” Clifford’s petition is over 100,000 signatures strong and well on its way to meeting its goal of 150,000 signatures. On the Change.org site, Clifford identifies the overwhelming barriers that prevent Native women from obtaining the emergency contraception pill known as Plan B.

Sometimes called the morning-after pill, Plan B is legally available over the counter to any woman age 17 or older and to women age 16 and younger with a prescription. It is effective in preventing pregnancy up to 72 hours after intercourse occurs. Plan B is routinely given to American women after a sexual assault where pregnancy may occur. Despite the fact that 1 out of 3 Native women will experience rape in her lifetime, the Indian Health Service does not make Plan B readily available.

It makes sense that Clifford is using an online petition to create change in Native women’s lives. She first heard of the NAWHERC report documenting the injustice rape victims who seek Plan B on reservations suffer via Facebook. Clifford says she “liked” the NAWHERC page and had been following it and the work of Charon Asetoyer, executive director of the NAWHERC on the Yankton Sioux Reservation in Lake Andes, South Dakota, closely. Stunned by the content of the roundtable report on Plan B, Clifford decided to try an experiment in her hometown of Kyle, South Dakota.

Though she was not in need of the medication for her own personal use, Clifford visited her local IHS office in Pine Ridge and requested Plan B. Clifford says she was told that the midwife was unavailable and that she would have to leave the reservation and travel about 40 miles, each way, to get Plan B over the counter. “When I was told I had to drive so far to get Plan B I felt frustrated and as if nobody cared,” Clifford says. “I do feel like women who need access to Plan B and don’t have the resources, such as a vehicle or gas money, are dehumanized.”

One of the reasons many activists consider Native women’s lack of access to Plan B both a legal issue and a human rights issue is the high incidence of rape in communities where Native women live. With sexual assault occurring in 1 out of every 3 female residents, women on reservations face the same reality women experience in war zones.

“I already knew this statistic of 1 in 3 before the roundtable report,” Clifford says. “I think most Native women are aware without a report that they have a high chance of being raped or sexually assaulted. This statistic is not surprising to me. I live this reality.”

Clifford believes rape victims are further victimized by IHS when they are denied access to Plan B and hopes her petition will raise awareness and “push IHS to offer Plan B without a prescription.” On the Change.org site, Clifford addresses Dr. Yvette Roubideaux, the Director of IHS, and insists Roubideaux has the power to “issue a directive to all service providers that emergency contraception be made available on demand — without a prescription and without having to see a doctor — to any woman age 17 or over who asks for it.”

While Clifford would love to see IHS develop 24 hour emergency care centers devoted exclusively to the health of women, for now she only asks that Native women enjoy the same legal right to Plan B that all American women have. “Plan B is not an abortion pill,” she explains. “Plan B is a higher dose of birth control which helps prevent an unwanted pregnancy up to 72 hours after unprotected sex.”

By seeking to advance the cause of victims of sexual assault, this young Oglala Lakota woman has taken Native women’s truth to proactive power. “Charon told me Dr. Susan Karol, who is the Chief Medical Officer at IHS, sent her a letter in late May in regards to enacting policy to ensure Plan B is available OTC,” Clifford says. “However, I will not feel I’ve achieved the change necessary until I am able to walk into the IHS clinic and receive Plan B over the counter with no questions asked.”

If she is successful, every woman, regardless of place of residence, will have a greater chance of getting and taking Plan B within the crucial 72 hour window of time needed for it to be effective. This would be revolutionary for dispossessed women living on reservations. “I can only hope,” Clifford says, “that the petition creates the change I seek.”

Clifford’s Ongoing Fight for Women’s Control Over Their Bodies

While Clifford has only recently become active in the fight to make Plan B available, for six years she has worked to liberate Native women living on Pine Ridge from state control of their bodies.

Women on Pine Ridge are unable to obtain Plan B to prevent the further victimization of an unwanted pregnancy following sexual assault; and, after an unwanted pregnancy occurs because they can’t access Plan B, they are also unable to have a safe, legal abortion on tribal land. In addition, few options are available to Native women seeking to terminate their pregnancies by leaving Pine Ridge, as it has also become increasingly difficult for women to have abortions anywhere in the state of South Dakota.

In 2006, South Dakota legislators proposed a law that would ban all abortions, including abortions for pregnancies that resulted from rape and/or incest. In response to the bill, Cecelia Fire Thunder, the first woman president of the Oglala Sioux tribe, publicly stated her interest in opening a women’s health clinic on Pine Ridge property. This facility would offer women’s health care to non-Native women as well as local residents. However, the Pine Ridge community was divided in its support of Fire Thunder’s proposal, and she was eventually ousted from her position as tribal leader. A PBS Independent Lens documentary film called Young Lakota is in production and chronicles the roles Clifford, her twin sister Serena, and their neighbor Brandon Ferguson played in this political firestorm.

Clifford, who was pro-life when she was a teenager, says she attended an “open discussion” organized by Fire Thunder to discuss her idea for a women’s health clinic with local residents. Clifford says she met the Young Lakota film crew at the open discussion, and their questions about her level of involvement in the debate compelled her to learn even more about the abortion issue. “I wasn’t really aware of how necessary abortion can be to some women,” she says, “but I formed my opinion that they can’t outlaw abortions. It seemed really outrageous.”

Referring to her earlier pro-life stance, Clifford adds, “Educating myself led me to change my mind. When I really thought about putting myself in the shoes of a woman who was raped and unable to abort an unwanted fetus, I could not fathom the situation. There are other instances, such as an ectopic pregnancy, that endanger a woman’s life and an abortion is necessary.”

As events began to take shape following Fire Thunder’s proposal for a women’s health clinic on the reservation, Clifford and her sister became involved in the fight to make basic obstetrical and gynecological health care, including abortions, available on Pine Ridge.

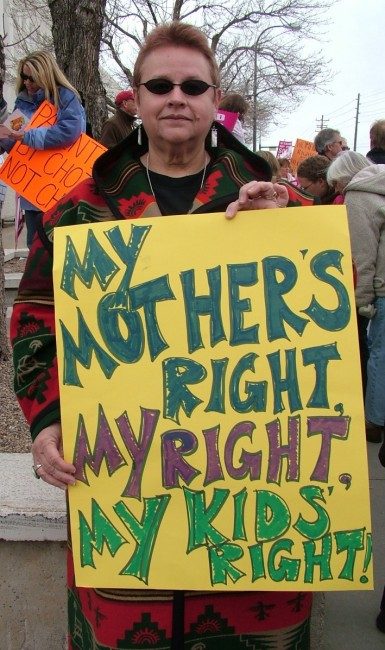

“We participated as best as could,” Clifford says. “We went to the tribal council meeting where they called for Cecelia’s impeachment. I was planning on reading a statement, but they kicked us out. From then on I began to form more of my opinion around women’s rights. My twin and I also did some protesting against the ban in 2006, in Rapid City. We both volunteered our time to post signs across the reservation [not an easy task considering the reservation is almost 2 million acres]. We did what we could.”

Clifford says she experienced some harassment as a result of her activism. She says someone threw a diaper at a sign supporting Fire Thunder’s position that the twins had erected in their front yard. One night, she adds, someone kept driving past their house, frightening Clifford’s mother enough for her to order her daughters to take the sign down.

Though they obeyed their mother, this silencing of the young women’s ideas continued in public forums where rigorous discourse is meant to take place. At Fire Thunder’s impeachment, Clifford says local residents shouted obscenities at the twins and accused Clifford of baby-killing before ejecting them from the meeting.

“Cecelia’s proposed women’s clinic was not even in writing!” Clifford says, incredulous at the level of tension on Pine Ridge at that time. “It was only something she said, and she was impeached for the mere idea. At the impeachment there were outside people giving out signs saying ‘Children are Sacred’ and bumper stickers too. At the hearing a lot of people were wearing pro-life tee shirts.”

Visible reminders of that contentious time remain. “Just yesterday in Rapid City,” Clifford says, “my twin and I saw an old bumper sticker from the 2006 ban that said ‘Abortion is Unhealthy for Women: Vote Yes on Six.’” Symbols like that could silence Clifford’s active participation in our democratic process, but she pushes past fear to articulate her support of accessible women’s health care.

Clifford stands with a slingshot aimed at the giant. Instead of stones, she lobs words, and the elegant wit she employs helps boil the biggest issues in this battle down to single, clear drops: “The latest law to be enacted in South Dakota, just the other day, mandates that doctors ensure a woman who is seeking an abortion is not being pressured by anyone to have the procedure,” she says. “It’s this big awkward paradigm. Why not mandate that a pregnant woman seeking prenatal care is positive that she wants to have a child?”

About the potential for conflict as the debate surrounding women’s health continues in her home state, Clifford says, “Sometimes I wonder what people might say behind my back, but I’m not really worried. I’m tired of worrying about what other people think when I’m speaking about issues that are important to me. The film is going to be finished soon, and it will bring more attention to us. I think it’s an opportunity for me and Serena, and other women too. I hope it opens things up even more.”

“There is a chance I could face backlash,” she continues, “it could be violent. But it doesn’t scare me as much as thinking about a woman who has been raped and can’t get healthcare. I’m much, much more scared about that. Which is more important?”

Published on HuffPost.com by Eisa Ulen, September 19, 2012.