By Eisa Nefertari Ulen – Published in The Defenders Online, May 14th, 2010

By Eisa Nefertari Ulen – Published in The Defenders Online, May 14th, 2010

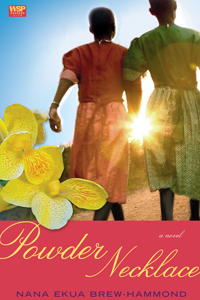

Powder Necklace, a young adult chapter book by first-time novelist Nana Ekua Brew-Hammond, explodes an awful reality for elite boarding school girls in Ghana. Despite the headmistress’ relentless insistence that her students are “duchesses” and the Dadaba Girls’ Secondary School is “The best” in the country, she can’t seem to summon the most basic of all human needs for the young women coming-of-age there: water. Forced to beg, borrow, and steal enough just to take a proper bath, Brew-Hammond’s characters face challenges most Western readers will find difficult to imagine – which makes the author’s decision to make the main character a British-born girl of Ghanaian descent a superb choice.

Teen-age Lila is sent by her divorced mother to live in Ghana before she becomes “spoiled” by a local London “Bus Stop Boy.” That she is going to live in Ghana is such a surprise to Lila that her suitcase is filled with sweaters and jeans, clothing that will be useless to her in hot Ghana. Lila’s mother doesn’t inform her that she is going to board a plane to Africa until they are well on their way to the airport, a deceit that is just the latest in a series of disappointments that come from her controlling, lonely single parent. Lila’s distant father, who has remarried and started a new family in New Jersey, cannot rescue this protagonist from a punishment she receives even though she has done nothing wrong.

Lila’s aunt picks her up from the airport in Kumasi, and every sight and smell that assaults Lila is described in uncompromising detail. The line of Ghanaians at customs “could have been called the Ugly Queue: long and lined with short sweaty men and women wearing bad wigs fussing over fidgeting children.” The terminal itself is “airless” and Lila “sniffed around, trying to place the source of the garlicky, boiled-egg, sulfur-hair-pomade smell in the room.” Helen, a white airline stewardess, tells Lila, “These guys don’t wear deodorant.” Even Lila’s kind Aunt Irene wears “gold rings and gaudily long nails…high heels and tight jeans that made her legs look like drumsticks.”

When Lila makes friends with one girl at Dadaba, a “Broni,” or Black-White girl like herself, she learns that Aunt Irene has chosen not to send her to the school populated by the children of diplomats and the corporate elite where locals who work on school grounds are treated like neo-slaves. The point is for Lila to become more Ghanaian, and Lila’s mother and Aunt Irene want her to relinquish some of her Western elitism, like her request for a hot shower after the long and completely unexpected plane ride to a land that is, to her, foreign.

By the middle of the story, they have, to some extent, succeeded. When Lila returns to her aunt’s for Christmas, she thinks differently about Enyo, the maid her same age who works there: “Now that I knew what it was to fetch water in a heavy metal bucket, sweep a plot with a short broom, and wash my clothes in hard water that didn’t easily form suds, I appreciated that she did it better than I did.” And by the end of the book, after a reunion with her mother and her father’s family, Lila can rethink the symbolism of the powder Dadaba girls use on their necks to mask any dirt or odor that clings to skin when water is a scarce commodity: “Maybe the point was to keep your head up – wear your powder necklace – no matter what. No matter what.”

This pride is ultimately what guides the narrative as Brew-Hammond explores displacement and identity, loss and reconciliation, initiation to womanhood and the lost innocence of a pampered Western girl. She ranks with many first and second generation immigrant American writers who examine similar themes, particularly displacement and identity, in their fiction. And like many of these authors of immigrant narratives, Brew-Hammond has produced fiction with some basis in her own life.

Like her protagonist Lila, Brew-Hammond attended boarding school in Ghana. The grasp at the authentic self, an identity made elusive by her marginalization as a woman of color in Europe and America as well as her marginalization as a woman of the West in Africa, is familiar to her. Brew-Hammond, who was born in The United States, often traveled through England during her travels between New York and Ghana.

Perhaps more important, Brew-Hammond remembers what it’s like to grow up, and she writes with gusto about issues of concern to young, emerging women the world over, issues including boys, friendships with other girls, and the desire to wrench free from the grip of flawed parents and come into one’s own. These universal experiences make Powder Necklace a good read for teen girls everywhere, but it is the specific experience of a British girl of African descent sent back to her parents’ homeland that make this work special.

Powder Necklace is unrelenting and unself-conscious in its exploration of teen life and all that is difficult in the West African nation better known to most Americans for independence leader Kwame Nkrumah and Pan-Africanists Marcus Garvey and W.E.B. DuBois. Powder Necklace does not even mention these 20th century black male leaders, as Brew-Hammond’s characters are much more concerned with surviving Dadaba Girls’ Secondary School than with which NAACP co-founder was buried in their country nearly half a century ago. A stunning absence of both white liberal guilt and black romanticization of Africa make this YA novel honest, which makes Powder Necklace a significant work of fiction.