By Eisa Nefertari Ulen, published in The Defenders Online, September 11th, 2009

By Eisa Nefertari Ulen, published in The Defenders Online, September 11th, 2009

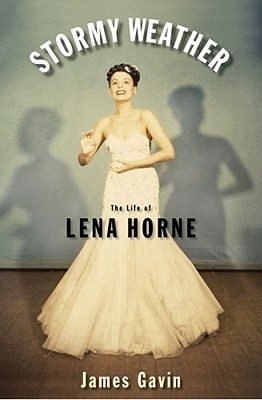

As journalist James Gavin spotlights in his most recent book, Stormy Weather: The Life of Lena Horne, the music industry critically judges black women dancers by their looks, demanding that they “be red hot and sexy.” Though at least one admits to turning “the occasional trick” to get by, the goal, for many of these women, is “marrying up” to a famous actor, popular musician, or even rising political star.

But Stormy Weather isn’t about the entertainment industry of 2009, or even 1999. The dancers Gavin writes about who gyrate and shimmy for low pay aren’t booty-shaking video vixens, they’re chorines of the 1930s Cotton Club, each of whom “had to lift her skirt and show her legs” at the audition just for the chance to dance to the tunes of such legends as Duke Ellington.

The possibly gay singers and actresses aren’t Hip Hop stars who challenge the hetero-normative standard of delicacy and fragile beauty in women performers; they’re Ma Rainey, Bessie Smith, Ethel Waters, Josephine Baker, and Billie Holiday. They’re even Ava Gardner and Kay Thompson. They’re even Marilyn Monroe.

And, in this book, the NAACP isn’t the organization celebrating 100 years of monumental achievement, yet forced to justify its relevancy to a media that repeatedly asks if we still need black civil rights leadership. This is the mid-20th century organization that lobbied to create black stars and for those stars to have the opportunities to play more than maids and butlers.

Walter White, NAACP Executive Secretary from 1931 to 1955, acted as queen-maker, muscling MGM to make Lena Horne the African-American starlet of her day. Gavin writes that White selected Horne because “she wasn’t a mammy or a whore; she didn’t growl the blues or speak in Negro dialect. Instead she sounded like an educated, well-bred young lady, one whom a few white families might even welcome in their homes.”

Horne sounded like a lady because she was a member of the bourgeoisie, a grand-daughter of the respectable, activist, and always proper Horne family. The trail-blazing actress’ middle-class background is given sufficient attention in this voluminous biography. Just when a young Miss Horne was about to sign with MGM, Lena’s father, Teddy Horne, entered the office of arguably the most powerful man in Hollywood history, Louis B. Mayer, and said, “It’s a great privilege you’re offering my daughter. But I can buy my daughter her own maid.” Teddy Horne told Mayer his daughter would not “play a maid or a jungle maiden,” and she never did.

In an appearance on the Dick Cavett television talk show decades later, in 1981, Horne would say, “I don’t think Mr. Mayer had ever been approached by a black man like that.”

MGM produced one classic film starring Horne, Cabin in the Sky, in 1943. Her signature film, Stormy Weather, was produced by 20th Century Fox, also in 1943. These are the only two films she ever starred in. The NAACP had helped get Horne in, but couldn’t get her further up. Racist Southern censors, the demands of black propriety, and, Gavin asserts, even Walter White frustrated Horne’s ambitions.

Horne would mostly get bit parts signing a song or two in the MGM productions she appeared in after 1943. Her roles were easily excised by Southern censors who would sooner cut a beautifully elegant black woman from the film than show her to Southern whites, or to Southern blacks. Her name would even be blacked out of movie posters in the theatres below the Mason-Dixon line.

But, according to Gavin, some of the censorship came from the NAACP’s Walter White. In perhaps the biggest professional regret of her life, Horne turned down the opportunity to play the lead in St. Louis Woman, a Broadway stage production written by Harlem Renaissance luminaries Countee Cullen and Arna Bontemps. An MGM vice president, Sam Katz, “formed an outside company to mount the show. Horne would play “a femme fatale who sparks a love triangle between Lil’ Augie, a lovable jockey, and saloonkeeper Biglow Brown” in this all-black musical.

In this book, organizations like the NAACP are the vanguard in the ongoing quest for civil liberties and open the door for African-American achievement. Alternately—or sometimes simultaneously—this same organization is so powerful and controlling that the folk who work in front of the camera in black Hollywood, Gavin reports, “can’t get tipsy in public” or “have a sex life that is slightly indiscreet” because of the pressure to be a “symbol.”

Then NAACP President Walter White read the play and declared “that it depicts the principal character of Della as a good-looking but loose woman of the sporting variety whose chief ambition is to have and be had by the gambler with the most money.” Because White had elevated Horne to the level of “something of an idol to her people, a symbol of the highest type of Negro womanhood,” the role simply would not do.

Pearl Bailey got the lead instead. Critics were mixed in their response to the play, which closed after just three months. Years later, Gavin writes, Horne still “groused about how the NAACP had blocked her from doing a show written for her—and how the Urban League had ‘come down hard’ on her for thinking about doing an all-black musical.” But despite growing resentments, Horne maintained her relationship with both.

The NAACP member Horne most admired—and deeply mourned when he was brutally murdered in 1963—was Mississippi field secretary Medgar Evers, who had helped launch Horne’s activism during her 1963 trip to the South to support the movement with former Delta Sigma Theta president Jeanne Noble and jazz artist Billy Stray horn.

Evers’ optimism and personal power, the children Horne met who learned how to protect themselves from jabs and kicks as they planned to picket a local JC Penney’s, and the knowledge that Evers’ home had been firebombed days earlier all moved her tremendously. Prior to this trip, Horne had been part of a group that included activists James Baldwin, Lorraine Hansberry, Dr. Kenneth Clark, Harry Belafonte, white film actor Rip Torn, June Shagaloff of the NAACP, and Jerome Smith of CORE, as they gathered to lobby then Attorney General Robert Kennedy to do more on the issue of civil rights. After Mississippi, Horne vowed to deepen her commitment.

Horne, who greatly admired family friend Mary McLeod Bethune, founder and president of Bethune-Cookman College; and had discussed race with First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt; stood behind the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr., when he gave his “I Have a Dream” speech. She shed tears when Malcolm X was assassinated at the Audubon Ballroom in 1965. But there was more to Horne than her activism, and the noble and the salacious are given equal treatment in this gripping narrative.

Lena Horne also cheated on her husband, remarried a white man whom she later emotionally abused, probably had an affair with married boxing legend Joe Louis, and definitely was absent from her children’s lives. Stormy Weather, an unauthorized biography, presents a complete Horne: whole and human. It tells how the goddess was made, why she ascended, and what brought her down.

In many ways, Gavin’s book tells the story of black America from the last lights of the Harlem Renaissance to the shining star that is the nation’s first black president. By focusing on Horne, the trailblazer / activist / singer / actor/ dancer / icon, her rough road from the indignities of the segregated Cotton Club to an Upper East Side home is made clear. Horne paved that road for actresses like Cicely Tyson, Halle Berry, and Angela Bassett. The reader emerges from this narrative full of gratitude for Lena Horne and so many others for getting us from there to here. The psychological and emotional toll of the journey on even this black woman, who was among one of the most privileged of the 20th century, has been exacting—impacting family, friendships, and, according to Gavin, Horne’s sense of self.

Because so very much that Horne suffered still plagues black people, black entertainers, black women today, Stormy Weather: The Life of Lena Horne also makes clear how far we have left to go on that road—and how rough the days and nights can be as we travel along together.

Comment(s)

- § James said on : 10/17/09 @ 17:53

I’m currently reading this point, although it lacks the flow and style of Donald Bogle bios of Black Hollywood it is an interesting read if for no other reason it corects some myths about Horne’s life. But honestly Gavin isn’t much of a writer.