By Eisa Nefertari Ulen, published in The Defenders Online, December 18th, 2009

By Eisa Nefertari Ulen, published in The Defenders Online, December 18th, 2009

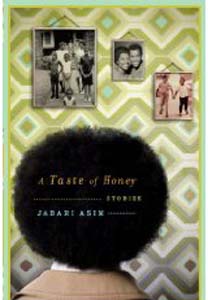

It is entirely fitting that Jabari Asim’s debut fiction, A Taste of Honey, is published in this, the year after Change. Everything is different now that the President of the United States is a black man. Everything changes in Asim’s collection of connected short stories, too—not because a leader is on the rise, but because one is shot down.

It is 1967, the year before Martin Luther King, Jr.’s assassination brought America very different kind of change. King’s assassination brought us burning and looting, but Asim remembers the innocence just before everything exploded, when black communities were thriving with locally-owned businesses and all the boys on the block had nicknames.

In Asim’s narratives, everyone in the neighborhood is close enough to be familiar. Boys grow into manhood under the watchful gaze of elder porch-sitters whose parents had joined the Great Migration. But all is not bucolic in Asim’s aptly-named Midwestern town of Gateway.

The same boys who watch Mr. Terrific and Captain Nice on TV also witness police brutality. Fists are pumped because, as one young son realizes to his amazement, on the white side of town, stores are “bigger, brighter, and cleaner… Oblivious to the hostile stares of shoppers and employees alike, he gaped wonderingly at the fresher produce.”

Violent whites attempt to circumscribe black achievement with mean looks, poor services, sexual assault, police batons, and hunting rifles. Even in the segregated all-black community where Asim’s characters live, white ghosts, real and figurative, haunt African-American strivers.

In one story, “Ashes to Ashes,” vigilante horrors help spur the migration to towns like Gateway. Asim leaves the reader with no argument against the racial politics of the people on the black side of town, where even the most conservative residents can “see the pale hand of the Man in everything…Ask old folks for evidence to support their claims and they’d say, ‘Just keep on living. You’ll see. ’”

Asim captures the mid-twentieth century, the mid-west, the space we occupy between our own love and the hate of the harsh world outside communities like North Gateway.

He is also honest about what we did wrong as we shifted from the year before King’s death to everything after. The Warriors, a local, Panther-esque organization, stumbles. They reject stability and tradition – and that means rejecting weddings, baptisms, and regular jobs that pay the bills. Meanwhile, marriage and family march strong into a kind of power that could never be expressed in a tight fist. Asim makes a case for church, for school, for lemon pie. Surely, these are the things we can count on not to change, but to endure.

With a 20/20 hindsight that that has seen the disintegration of The Movement in the 70s and the explosion of crack in the 80s, 90s bling and murder rates rising (again) in the 00s, Asim looks back at The Revolution. A devoted husband and father and author of ten books, he nostalgically evokes a different revolution. He remembers the revolutionary power of Black song stirring folk to catch the spirit—even when they stand in the street outside the church. He knows the revolutionary fervor of black mothers and fathers fiercely protective of their own. And Asim bears witness to, and celebrates the triumph of the most revolutionary act of all: Love.

Q: You wrote The N Word: Who Can Say It, Who Shouldn’t, And Why, so the exchange in Day Work between a self-styled but undisciplined revolutionary and the leader of the Warriors is especially significant because this is the only place in A Taste of Honey where the B-word and N-word are used, just as the more reckless character is poised to riot and cause chaos in the Gateway community. How important is that scene to you?

A: I have always been struck by Bayard Rustin’s criticism of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), which he said was sometimes hampered by a desire to offer psychological solutions to problems that were profoundly economic. Pee Wee, the character who uses the n-word, consistently confuses racially-charged rhetoric with actual political strategy. Talking tough eases some psychological need of his, but does nothing for the community he supposedly serves. He is unable to see beyond the visceral and emotional and thereby recognize the real work that organizations like his need to do, and his language reflects that lack of vision. I wanted Pee Wee to represent a decline in the kind of activism that had been flourishing in some urban communities, when service and sacrifice were supplanted by aimless, thoughtless rage that quickly turned inward.

Q: One theme in your collection of short stories seems to be that, while political activism is important, real revolution takes place in marriage. What do you think were the major failures of the urban activists of the 1960s and 1970s? What were their biggest triumphs?

A: I’ve always been bemused by brothers who talk a lot about nation-building and institution-building, but are unable to commit to the most fundamental unit of nation-building: their own families. They go on and on about “the nation” and “revolution” when the most revolutionary thing they can do is devote themselves to their wives and children—the very behavior, in fact, that our traditional oppressors have wanted us to avoid more than any other. I wanted to suggest that to engage in mindless promiscuity and absentee parenting is the same as implementing a white supremacist agenda. I also wanted to shine a light on the kinds of men I knew and admired as a child, men like my father, who lived lives of quiet integrity.

As for the activism of previous decades, I believe the triumphs far outweigh the failures. Having said that, I also believe that the black leadership model, once based on selflessness and service (and embodied by folks such as Joanne Robinson, Ella Baker and Fannie Lou Hamer, to name just a few) has been almost completely supplanted by bluster, false bravado, and a desire to be rich and famous. In many cases, it’s difficult to distinguish between black entertainers and black people who posture before the television cameras as “leaders,” “spokespersons,” and “pundits.” I also wish the activism of the 60s had placed greater emphasis on an activist-entrepreneur model instead of an activist-consumer model. Culturally speaking, that would call for less reactionary boycotting of racist storytelling and more pro-active, self-generated storytelling.

Q: Gateway is located in the mid-west, and it also acts as a temporal space through which the black community shifts from the past of Emancipation and Jim Crow to the post-Civil Rights Era and a return to black families like the Obamas. Did the 2008 presidential election and the presentation of solid black family life on an international stage influence your work?

A: I had actually finished the manuscript for A Taste of Honey before the Obamas seized the national spotlight. I’ve written all of my books from my perspective as a husband and father, and this one was no different. I respond well as a reader to portrayals of black men and women who bravely take on the challenge of love and monogamy, and that affinity tends to fuel my impulses as a writer.

Q: You are the author of two nonfiction books, five children’s books, an essayist, and a poet. How and when do you manage to generate so much work while maintaining your home life as a husband and father of five?

A: Please don’t forget Not Guilty, my first book for grown-ups. And I have two more children’s books coming out in April. When my wife and I had just two children (many years ago), I was laid off from my job as a reporter at a black weekly newspaper. I couldn’t find another job as a writer for two long years. I vowed that if I ever got another opportunity to write for a living, I would work until I dropped. I used to pray for the chance to be busy, and once I got busy I never complained about it. I tend to write in streaks, as opposed to writing every day.

I wrote much of A Taste of Honey while working on The N Word. I took six months’ unpaid leave from The Washington Post, wrote nonfiction in the mornings and fiction in the evenings. Typically I might write all day Monday and Tuesday, and not return to my computer until Friday. None of it would be possible without my understanding kids and my brilliant wife, Liana, to whom all my books are dedicated.

Q: You’re also former deputy editor of The Washington Post Book World, former vice president of the National Book Critics Circle, and Editor-in-Chief of The Crisis. What major trends do you see in books publishing and for black authors in particular?

A: It’s never been easy for black writers of literary ambition, whether they work in fiction or nonfiction, and the present picture is no rosier. With some exceptions, the book industry in general has undergone a real shakeout, resulting in fewer deals and smaller advances. I think this will affect black writers disproportionately, in part because publishers have rarely seen us as capable of attracting non-black readers. I’m not the only black author who will tell you that some of my best audiences have been composed of readers with all kinds of ethnic backgrounds, but somehow publishers continue to fail to notice the diverse markets to which we can stake a claim. Whereas recent years have been relatively prosperous for creators of so-called street lit, we’ll see a lot fewer titles in that category as well. There has always been an appalling shortage of black people in decision-making positions inside publishing houses, and now we have the fewest in recent memory. Some of them do absolutely terrific work championing black writers (I did the same thing when I worked at The Washington Post), but they can only do so much. At the same time, smaller houses such as Akashic and Agate have become reliable sources of high-quality black writing. I believe we’ll see the emergence of similar enterprises, with some of them operating as writers’ collectives.

Comment(s)

- § Helen W. Mallon said on : 12/28/09 @ 08:54

Great interview, Eisa. Thanks! I’ve been out of touch but haven’t forgotten our meeting at AWP.